By Bob Fisher and Thomas White

Ken Burns has produced and directed 27 documentaries on subjects ranging from the Civil War to the Prohibition Era to baseball. He has earned two Academy Award nominations, five Emmy Awards and seven other nominations. Burns was the recipient of the IDA Career Achievement Award in 2002.

The Roosevelts: An Intimate History is the next chapter in the evolving story of his career. The seven-episode,14-hour documentary, which premieres September 14 on PBS, takes audiences on a 100-year journey with Theodore, Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt. It was produced by Burns' company, Florentine Films, and WETA-TV, the PBS affiliate in Washington, DC.

The documentary begins with the birth of Theodore in 1858 and concludes with the death of Eleanor, his niece, in 1962. Burns says that this ambitious endeavor was a work-in-progress for about seven years. His longtime collaborators—writer Geoffrey Ward, producer/editor Paul Barnes and cinematographer Buddy Squires—played significant roles.

"Geoffrey and I had been talking about this since we began collaborating during the early 1980s," Burns says. "For a long time, we thought it would just be about Franklin Roosevelt. Geoffrey has written two books about him. We decided it would be more interesting and meaningful to make a documentary about the complicated, intertwined relationships between Theodore, Franklin and Eleanor. They were exceptional people who tackled daunting challenges with ingenuity and humanity."

The series includes a treasure trove of archival photographs, drawings, newsreels and other motion pictures that documents the lives of the Roosevelts and the evolving history of their times.

Doris Kearns Goodwin and 14 other historians offer compelling insights in The Roosevelts: An Intimate History. The interviews were filmed at locations where history happened, including a Roosevelt family compound in Hyde Park, New York; Theodore's home on Sagamore Hill on Long Island, New York; and Franklin's summer home on Campobello Island, off the coast of New Brunswick, Canada.

Peter Coyote narrates the screenplay, while Meryl Streep portrays Eleanor Roosevelt in readings from her personal letters and writings. The voiceover cast also includes Paul Giamatti, as Theodore Roosevelt, and Edward Herrmann, as Franklin Roosevelt.

The first three episodes of The Roosevelts: An Intimate History cover Theodore's rise to power, from New York City Police Commissioner to New York State Governor, to war hero in the Spanish-American War, to US vice president and, finally, to the presidency, which he assumed upon President William McKinley's assassination in 1901. Theodore was subsequently elected president in 1904.

President Theodore Roosevelt, 1903. Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Theodore Roosevelt was a trust-buster, who fought corruption in the railroad, oil and other industries. He championed the Food and Drug Act, which gave the government authority to assure public safety. And he established 125 million acres of national forests and parks.

The balance of the series is devoted to Franklin—Theodore's fifth cousin—and Eleanor. Franklin served as assistant secretary of the Navy in Theodore's administration. Following a run for vice president in 1920, Franklin was stricken with polio at age 39. The Roosevelts covers the FDR's unprecedented 12 years as US president, beginning with the Great Depression, which crippled the economy after the 1929 stock market crash; continuing with his ambitious New Deal program, designed to address the staggering unemployment and financial losses incurred by tens of millions of Americans; and highlighted by his extraordinary leadership during World War II.

The series concludes with FDR's death and Eleanor's emergence as a champion of civil rights and civil liberties. She also served as US delegate to the United Nations and as chair of the UN Commission on Human Rights. Prior to her passing in 1962, she chaired President John F. Kennedy's Commission on the Status of Women.

Delegate Eleanor Roosvelt at a meeting at the United Naitons, 1947. Courtesy of Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidnetial Library

There was something about the Roosevelts that, despite their patrician bearings, connected them with so many Americans across the classes. "There is something that each one of them says in their own way that is the key to this," Burns noted at a presentation at the Television Critics Association (TCA) conference held in Beverly Hills in July. "Part of what we do is, we engage in the mystery; we don't solve it. All of them had a similar idea: We share a sense of fairness and a sense of obligation to those less fortunate-and that speaks directly to what Theodore, Franklin and Eleanor were about and that equation of, essentially, a rising tide lifts all ships, which is the fundamental aspect of their philosophy. When FDR's funeral procession went by, a man collapsed; he was so overcome. A neighbor picked him up and said, 'Did you know the president?' And he responded, 'No, but he knew me.'"

But it is the "Intimate History" in the subtitle of the series that presented its greatest challenge for Burns and Ward-How intimate? How historic? "I spent 30 years writing about the Roosevelts," said Ward at the TCA conference. "[For this series] it was compression, and then trying to make it a family story, which no one had never done before. They all talked about each other all the time; they resented each other or loved each other. That was fun trying to braid that all so you had a real sense of how they lived their lives."

"This is fairly complex narrative," Burns added. "It takes three people-and by extension several dozen other people—and moves them through 104 years of familiar American history and tries to see it in another way. For us, it was unwrapping something. When you focus on presidents and wars and generals as our narrative history, you're asking questions like, What's the role of government? What is the nature of leadership? How does character inform leadership? How is character itself formed by adversity in life? What are the flaws? Are we expecting perfection in our characters? Or do we understand that heroism is a negotiation between strengths and weaknesses? This is a fine calibration on the part of a writer and a filmmaker in trying to get that balance correct."

"They are the boldest of the boldface names in American politics," Burns continued. "That tends to keep them at a distance. As we worked on the film, we found something that was familiar about them because of these things they were going through. The illnesses, the recoveries, the losses and betrayals: all of those things are very familiar to all of us. That became an anchor in which you could find purchase on these very complicated, and very famous, lives, and it somehow helped to take out the boldness of their boldface names."

Of course, the humanizing element in FDR's presidency was his debilitating fight with polio—a fact that is common knowledge today, but that was kept hidden by both the White House and the press that covered him.

"I think you'll have a sense all the way through of the extraordinary struggle FDR had just to get through the day and to pretend that nothing was bothering him," Ward noted.

"In the election of 1944," Burns added, "when he's running for an unprecedented fourth term and he's frail and very ill, he traveled to New York City in the pouring rain to nearly all five boroughs in an open car, with the Secret Service taking him off the trail and stripping him, giving him a shot of bourbon and putting dry clothes on him. He arrives in Ebbets Field and newsmen had to turn off their cameras, but there was enough in the margins to see."

It was that in-the-margins footage, those few seconds of FDR in all his infirmity and pain and disability just before the cameras were turned off, that made a crucial difference in showing us viewers the magnanimity and humanity of the man. Did Burns have any qualms about including this footage? "Not at all," he told the TCA audience. "I think it's so moving. We had pretty much finished the film when we discovered four seconds of footage from the University of Pennsylvania. So we cut into it the film—at a huge expense—but we felt it was hugely important. This is accidental stuff: A train in Bismarck, North Dakota, and a platform that's extending out, with two railings, and he suddenly lumbers down and in just a couple of seconds you begin to understand what an incredible effort it was. The Ebbets Field footage shows that it's beyond stunning that he ever made it out of bed any single day."

President Franklin D. Roosevelt returns from a fishing trip, 1934. Courtesy of Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library

But again, given that Burns and Ward have billed this series as "An Intimate History," how "intimate" do you get? What does "intimate" mean here? Where is the line between "intimate" and "history"?

"This was a huge debate within our discussions in the editing room," Burns recalled. "We didn't want it to be just The Roosevelts. We debated "intimate" because it does suggest the tabloid. At the same time, as you pursue the backgrounds of people, you're walking the razor's edge where you don't want to get into psychobiography—and I don't think we've done that—but you do want an understanding of where they came from and the kind of adversity they felt. The "intimate" part has do with trying to understand from the inside out, rather from the top down."

And despite the exhausting magnitude of The Roosevelts series, Burns is not slowing down. Future projects include major series on country and western music and the Vietnam War, as well as a film on Jackie Robinson. Burns is also serving as executive producer and senior creative consultant on Cancer: The Emperor of All Maladies, based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning book by Siddhartha Mukherjee.

"I'm working on seven films right now," he said. "It's 24/7, but if you love your work, you don't spend the day working. We love nothing more than being in the editing room working ten hours a day trying to make a film better, and we're doing it right now on our Vietnam project. We're always at max speed in that way."

Editor's Note: And if you want to find out more about Theodore Roosevelt, you might want to check out the new edition of Harrison Engle's The Indomitable Teddy Roosevelt, distributed by Millennium Entertainment. This fifth edition will hit the streets October 28.

Bob Fisher has written more than 2,500 articles about narrative and documentary filmmakers over the past 50 years. Thomas White is editor of Documentary magazine.

Filmmaker Gabor Kalman's monthlong visit to his native Hungary this past spring could be the subject of a compellingly dramatic and emotional narrative film. The movie would begin with a flashback to Kalman's birth in the town of Kalocsa, in 1934. Approximately 12,000 people lived in the town. Around 600 of them, including Kalman, were Jewish.

Thousands of Jewish citizens were murdered during the Nazi occupation of Hungary during World War Two. Kalman was one of the few survivors in his hometown.

Russia established an authoritarian communist regime in Hungary after the war ended. Kalman was a college student when dissatisfied citizens attempted to overthrow the government in 1956. The Russian army brutally suppressed the revolt.

Kalman managed to cross the border into Austria and migrate to the United States as a political refugee. He earned undergraduate and graduate degrees from the University of California at Berkeley and Stanford University before launching his career as a documentary filmmaker.

Kalman was a founding member of the IDA and served on its board for nine years, during which time he founded the David L. Wolper Student Documentary Awards. When he is not producing and directing documentaries, Kalman is teaching the next generation of nonfiction filmmakers—at USC School of Cinematic Arts, from 1987 to 2007, and currently, Art Center College of Design in Pasadena. Kalman journeyed to his homeland in 1994 and 2008 to teach classes as a Senior Fulbright Scholar at the Academy of Theater and Fine Arts in Budapest.

Gyongyi Mago, a high school teacher in Kalocsa, contacted Kalman in 2009. She was educating her students about the Holocaust and about tolerance, in an aggressively right wing country. She invited him to attend a memorial service in Kolocsa for local Jewish Holocaust victims, and Kalman decided right then to make a documentary about this extraordinary teacher.

Gyongi Mago, subject of Gabor Kalman's There Was Once...

Kalman was one of seven survivors who attended the memorial service, along with relatives of Holocaust victims. The memorial included unveiling a plaque containing the names of the victims who had lived in the city. "It touched me deeply," he recalls. "I remembered people's names."

The service was not without its unsettling disruptions. A woman who had come from the United States was hit in the head with a nut from a slingshot. A few blocks away, a neo-Nazi party held a rally.

Kalman and a local cinematographer filmed attendees at the memorial sharing memories and feelings during conversations with Mago. Upon his return to the United States, Kalman interviewed survivors and members of victim's families who had migrated to the United States and Canada.

He completed production of There Was Once... in 2011; the film is a project in IDA's Fiscal Sponsorship program. While the film played in theaters in North America, There Was Once... wasn't shown in cinemas or on television in Hungary, and there were no stories or reviews in the press. It wasn't acknowledged in any way. "I wasn't surprised; the subject is sensitive," Kalman says.

Then, in late 2012, Karyn Posner-Mullen, the public affairs counselor at the US Embassy in Hungary, contacted Kalman. "She said, 'This is a fabulous film,'" Kalman recalls. "I want to show it at every school. I almost asked her how an American diplomat could get my film into a school system run by an autocratic government. About a year and a half later, she invited me to come to Hungary and show the film to students at schools around the country to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the end of the Holocaust."

And so, Kalman made the journey and showed There Once Was... mainly to high school students in small towns and in the countryside. "I was extremely well received by many principals and students," Kalman recalls. "The mayors came to screenings in some cities. At some schools, I was cautioned not to think that everyone in the city was friendly to America or Jews.

Gabor Kalman (in brown blazer) and Karyn Posner-Mullen, public affairs counselor at the US Embassy in Budapest (in gray pantsuit) with teachers and students in a high school in Debrechen, Hungary.

"Gyongyi told me not to expect students in the countryside to ask questions, because they are usually shy," Kalman continues. "She was right. Teachers asked questions, but students didn't. The minute we stepped outside, there was a ring of students around me asking questions. Many of them had never heard of the Holocaust."

Kalman adjusted the presentations by limiting the time reserved for questions and answers after screenings. Afterwards, he would step outside, where he was invariably surrounded by students. Long discussions took place. "One day, I noticed that a young girl was staring at me," he recalls. "I caught her eye. She smiled, apologized for staring at me and said that she had never seen a Jew before. The tone in her voice was pure curiosity."

On another occasion, Kalman noticed two boys standing together and whispering to each other. He had a feeling they wanted to talk with him privately. "I discretely stepped around a corner," Kalman says. The boys followed him. One of them said they wanted his advice about an issue that they didn't want to discuss in front of other people. "He said that Jobbik was making its way into their school," Kalman recalls. "Jobbik is an extreme right wing political movement. Both boys were very emphatic about insisting that they didn't agree with Jobbik. They asked if there was anything they could do. I wanted to help them, but I didn't have an easy answer."

During a discussion after a screening at another school, a student asked Kalman what he thought Hungary is like today, compared to 1944. "It was a difficult question," he says. "I wasn't there to spread anti-government propaganda, but I responded truthfully and, hopefully, helpfully."

Gabor Kalman (left) discusses his film and the Holocaust with students in a high school in Pecs, Hungary.

Kalman recalled that there was an extraordinarily warm reception in one town by the principal and mayor, who delivered a beautiful speech. After the screening and question-and-answer session, Kalman thanked the mayor for his hospitality. "He looked at me and asked why the international press, the United States and other Western nations are turning against Hungary and blaming us for all the Jewish and gypsy issues," Kalman says with a tone of sadness in his voice. "He asked, 'Don't they kill Negroes in America?'"

Kalman also showed the documentary at several American Corners, which are American cultural centers sponsored by the US Department of State. There are 400 Americans Corners in 60 countries, including five in Hungary.

Kalman presented There Was Once... at a conference for Holocaust teachers, including Gyongyi Mago. "Hundreds of teachers from around the country were invited to the conference, with travel, hotel and other costs covered," Kalman says. "I wondered why only about 100 teachers showed up. Someone told me many teachers were afraid and others were not allowed to come, per their principals. I asked teachers what students are taught about the Holocaust. To my great surprise and dismay, I discovered that just a few hours in the curriculum are dedicated to teaching students about the Holocaust."

Gabor Kalman (left) with Holocaust survivor in Pecs, Hungary.

After the screening and discussion that followed, every teacher who attended the conference was given a DVD of There Was Once.... by the US Embassy. "I don't know if they are showing the documentary to students or if they threw the DVDs in the trash," Kalman says. "The right wing was always hanging over us. It was a very palpable feeling throughout my stay in Hungary. The prime minister recently said that he has had it with liberal democracies, which he described as a failing system."

"I believe that one person can make a difference, like Gyongyi Mago in her various activities," Kalman maintains. "I might not have changed everyone's mind, but I am hoping that we gave some students, teachers and other people something to think about."

Bob Fisher has written more than 2,500 articles about narrative and documentary filmmakers over the past 50 years.

The freeways of Los Angeles are its arteries, pumping a steady stream of cars to its sprawling extremities. So when traffic is blocked or slowed by an activity, it is newsworthy, as if the city were having a stroke. When for ten days in the late winter of 2012, a 340-ton granite boulder was moved on a custom-built, football field-sized, 206-wheeled tractor-trailer to a famed art museum as part of a permanent display the event was literally—pardon the pun—massive.

Levitated Mass, the new film by veteran documentarian Doug Pray (Art & Copy, Big Rig, Infamy, Hype!), recounts the story of the creation of the eponymous work by Michael Heizer, and follows the movement of the megalith from a quarry in the Jurupa Mountains in Riverside County to its permanent home at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). The film explores the communal effort required to achieve this giant enterprise, and delves into the recurrent debate of "What is art?" in novel ways.

On the phone with Documentary, Pray recalls the genesis of the film: "One day three years ago, Jamie Patricof, the producer, called me and told me that they were going to move this giant thing through the streets of LA and they would have to take down all the traffic lights. And it was for an art project. And it was immediately of interest to me because first of all, I've never done an art film. I've done films where I deal with artists, musicians and graffiti artists, and I've done plenty of interviews with painters, but I've never really done what we would call an ‘art film.' It's just a genre that I really wanted to delve into. And I've always wanted to do a portrait of LA, as a filmmaker, because I've lived here for 25 years. And the fact that it was a rock itself appealed to me, because I love geology-my father was a geology professor, and I grew up running around in quarries and dealing with granite, sandstone and limestone. There was just something elemental about it that appealed to me."

The film was not commissioned by LACMA—Pray clarifies that "it's an independent film; we made it and we own it"-but it did require a close collaboration with the museum. As Pray points out, "LACMA had been speaking to a few other filmmakers as well. They knew they wanted to cover this; they knew it was going to be a public spectacle, though they did not realize how much momentum it would build from night to night as the rock was moving. We went to LACMA and there was a whole vetting process to make sure that our intentions would honor the art and the artist, and that the project could be successfully pulled off and filmed right, because it's a one-time thing. I showed them my previous films, and I showed them that I had done a film about truck drivers [Big Rig] and art [Infamy]."

Although the doc gives a detailed history of Heizer's body of work, it is not a meditative portrait of the artist, but rather a kinetic snapshot of Los Angeles and LACMA. "I realized early on that I was not about to be making a deep, introspective, brooding art film about Michael Heizer's brain and all his inner struggles," Pray explains. "I was not going to get a five-hour interview that every documentarian wants. Some artists speak about their art, their lives and their work, and some don't. And Michael Heizer doesn't. He lets the work speak for itself, and he really means that. He is one of the most reclusive artists of our time, and we had full access to his process, which is really rare. So I had to change my attitude about what kind of film it was. But then there was the public, and they kind of made the rock their own."

Indeed, the rock acts as a Rorshach test, a blank canvas on which people can project their own interpretation. "That's what all art is, but even more so with this because it's so open ended," Pray maintains. "They projected everything they believed onto that surface. It was like a giant mirror. The people who were deeply religious were absolutely convinced that this was a sign from God. And in places like Bixby Knolls, they just treated it like a giant street party. Everybody made it into what they wanted."

In sharp contrast to the laconic Heizer is Michael Govan, the jovial director of LACMA. "When you are faced with a character who does not wish to talk about himself," Pray explains, "the very first thing you have to look at is, Who is around him? Who else is in the story? The contrast is amazing, and you can't really have one without the other. Every great artist needs somebody who is there, who understands them and promotes them and sells them—sort of like an actor and his agent. And Michael Govan has been a true champion of Michael Heizer."

Pray captures the Fitzcarraldo-like obsession of transporting a giant rock for a 105-mile journey at painstakingly slow speed, and the bureaucratic hurdles and engineering logistics behind such a feat. Even though the actual boulder was blown out of the granite quarry in 2005, it took seven years of research, planning and fundraising before it moved an inch.

"It's a positive movie about sticking to your ideas," Pray reflects. "I relate what happened with the rock a lot to documentaries, because documentaries take so long, and there are so many things that can happen where you lose your will and your way. There's something great about a guy [Michael Heizer] having an idea in 1968, and here it is in 2012. And Michael Govan thought the whole project was going to get destroyed by bureaucracy, because it was not going to be able to move. Even someone as energetic and successful as Govan thought this might not work, it might not happen. I love the fact that it has a moral: Stick to it; don't give up."

Once the boulder was moving, the controversy ensued.

"Anytime you make large public art that is conceptual, there is controversy," Pray admits. "So the film is about that, in a way—the failure or the triumph of public art. There's also political controversy from traffic patterns to those who were convinced this was a huge waste of money at a time when so many people were unemployed and the city needed so much help. Most of those reactions were misplaced or misinformed, because they did not understand that it was not public money that was paying for the rock. In fact, it was quite the opposite; the rock was employing lots and lots of people. It was private money paying for public employees, for the most part."

When asked about the logistics of filming a live event over ten nights, Pray admits, "It was pretty fun. We scouted the route in a lot of detail, so we knew where the next interesting view was, and it travelled at only five miles per hour, so there were ways we could get around and ahead of it. And we were embedded with Emmert International, so we did have full access to the move. We had three camera people: me; Chris Chomyn, the DP; and Edwin Stevens, who was my assistant and ended up filming a third of the movie. We split the coverage up. And we would jump in moving cars to film it rolling. Because I couldn’t be up during the day, Erin Heidenreich directed all of our daytime interviews, functioning as a second unit.”

As to the biggest challenge in making the film, Pray concedes, "Early on, the most difficult part was trying to get my head around the fact that I had wanted to do a certain kind of film, and I realized that it wasn't going to be that kind of film, and I had to change my mind as to what kind of film it would be—which is really a part of documentary filmmaking. It’s negotiating the difference between what you originally wanted, versus what you’re going to actually get, then changing your attitude and setting out to make that new film the best it can be. And hopefully that’s better than the film you had started out trying to make. And that transition is never easy; it's always like a gearshift. We directors are always hell-bent because we have a vision, and to change that vision mid-stream is always frightening. It involves a leap of faith."

Levitated Mass opens in Los Angeles on September 5 through First Run Features. For the national tour schedule, click here.

Darianna Cardilli is a Los Angeles-based documentary filmmaker and editor. Her work has aired on Bravo, A&E, AMC and the History Channel. Her articles have been published in Documentary, Dox, DolceVita and VivilCinema. She can be reached through www.darianna.com.

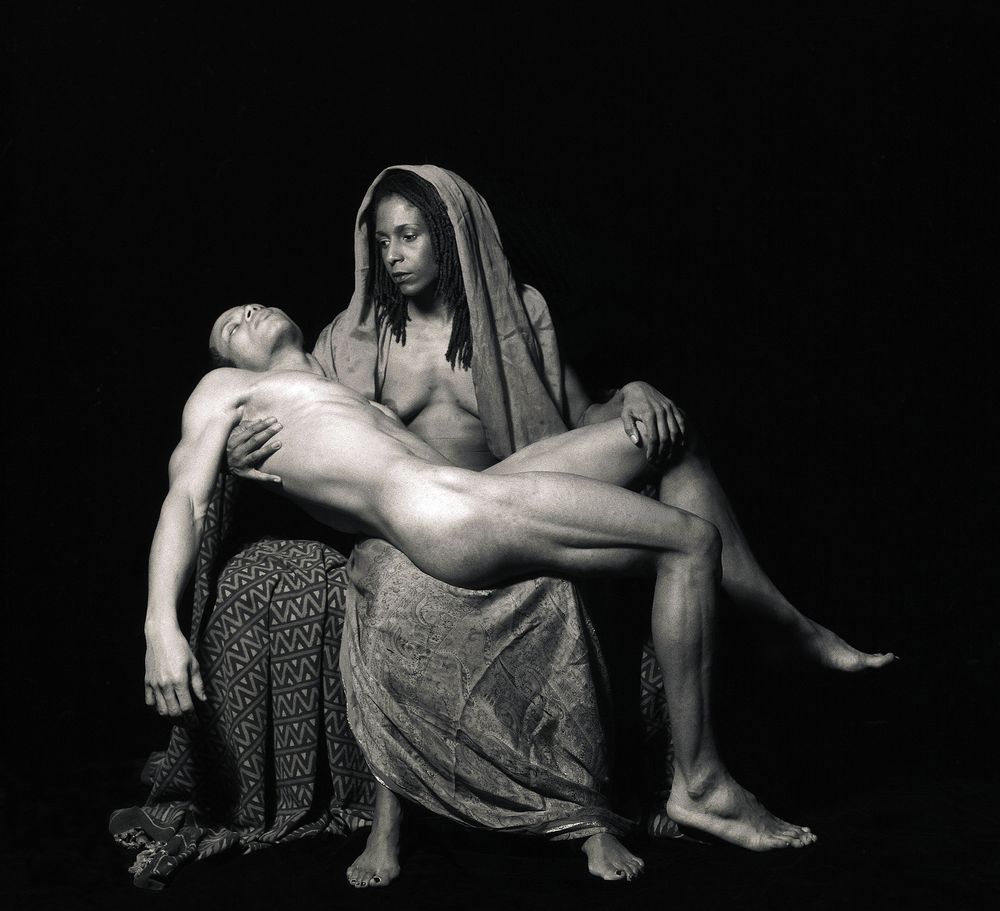

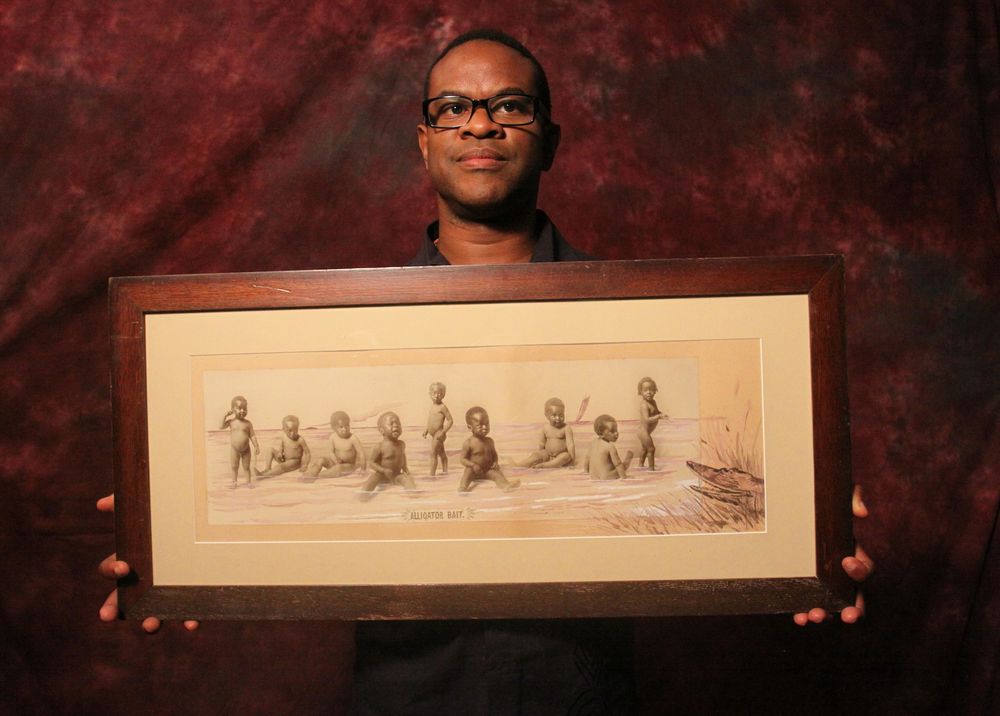

Photography serves to inform and educate; record and preserve moments for future generations; evoke memories; and document different communities, lifestyles and cultures. Award-winning documentary filmmaker, scholar and artist Thomas Allen Harris has a clear understanding of the responsibilities of photography, as demonstrated in his body of work, which is based on sharing personal journeys. He credits African-American leaders from the 19th century for their insight and understanding of the power of the images. "African-American leaders Booker T. Washington, W.E. B. DuBois, Sojourner Truth and Fredrick Douglass historically were all very concerned with image and photography, especially in the early 19th century," he explains. "It was the new media, like the Internet is for us now. They saw this as offering a possibility for us, for our emancipation." The larger society has interpreted this role differently throughout history, with its photographic depictions, both demeaning and horrific, of African-American life. This contrast between black and white underscores the struggle among the African-American community with a legacy of pride and shame. Harris challenges and examines the role of photography in his fourth feature-length film, Through a Lens Darkly: Black Photographers and the Emergence of a People.

Harris explored issues of identity and representation in his earlier work. His 1995 debut VINTAGE—Families of Value looks at three African-American families—including his own—through the eyes of LGBT siblings. He took this inquiry into identity and self-discovery further with his subsequent films, E Minha Cara (That's My Face) (2001) and Twelve Disciples of Nelson Mandela (2005).

Harris opens Through a Lens Darkly with a painful personal memory: He describes his father wiping Vaseline off his face and saying, "Do you want people to think you are a greasy monkey?" Harris confesses, "I'd rather not have to deal with all of the pain in public, but it's a sacrifice. Someone's has to do it, so I had to step up." Realizing his father's comment was rooted in a place of fear and a distorted negative self-image, Thomas sets out to address these feelings, taking a complex look at image.

Through a Lens Darkly was inspired by the groundbreaking book Reflections in Black: Black Photographers from 1840 to Present, written by scholar and photographer Deborah Willis, also a producer of the film. Harris, along with Willis, interviewed a total of 51 people and did extensive research for seven years, identifying over 20,000 photographs. During the course of the 10 years it took to complete Through a Lens Darkly, the project changed many times. "The film became about looking at the family album and who was represented," Harris says. It was important for him to introduce the film with a quote from writer James Baldwin because he speaks specifically about stereotypical images and distortions that are deeply rooted in the culture. "The brilliance of James Baldwin is his poetic and insightful analysis," Harris maintains. "And when we opened the edit room, we knew we had to start with his quote to set the film up."

The film presents a powerful, comprehensive visual examination of the African-American image from the beginning of the photography medium to the present. A community of African-American historians, artists, photographers and scholars, including Deborah Willis, Anthony Barboza, Lorna Simpson, Clarissa Sligh, Carrie Mae Weems, Hank Willis Thomas and Lyle Ashton Harris, discuss the power of the image and how it is used. Over 950 mostly original photographs of African Americans are shown in the film to assist in weaving stories of representation, exclusion, pride, dignity, pain, shame, hate and stereotypical depictions that have been prominent in American culture. The film reveals the hidden history of black photographers, the missing images from the family album, the work of LGBT artists and untold stories of black female photographers. The artists honor the late artist/photographer Roy DeCarava, highlighting his book The Sweet Flypaper of Life as a must-have for serious photographers.

One reason Harris understands the role of photography so well is that he too is a photographer; his grandfather gave him his first camera when he turned 6. Harris is also featured in the book Reflections in Black. When making Through a Lens Darkly, he discovered how little the general population know about the contributions of black photographers. "The majority of people can't name a single black photographer outside of Gordon Parks, and that's a real problem," Harris laments.

Harris also began thinking about conversations with people wanting to do something creative with their own family photos that would be of interest to their kids. He saw the potential to do an outreach project for Through a Lens Darkly through another medium, where families would explore their collection of photos. Working with producer Ann Bennett and the Bay Area Video Coalition (BAVC) Producers Institute, Harris developed a prototype online project called Digital Diaspora. It developed into a concept that might be described as "Antiques Roadshow meets StoryCorps." After showing it around, Harris was asked in 2009 to present a "live roadshow" at the Integrated Media Association's Public Media Conference in Atlanta, at which representatives from the African-American community were invited to participate. "People started paying us to come and do the Roadshow, and out of that we began to get amazing images of African Americans dating back to the 1840s," Harris recalls.

Harris and his team put Through a Lens Darkly on hiatus that year and shifted focus on the outreach project, Digital Diaspora Family Reunion (DDFR). "There is no way I can begin a new project at the end of the film, so we decided to do an outreach project that runs concurrently with the film," Harris explains. DDFR is a multimedia-driven social engagement project designed to connect people through stories and images to present a national family archive. "Several of those images made it into the film," Harris says. "We were filming it and creating social media with it and creating short pieces that we broadcast for YouTube." One project began to inform the other and both were moving forward. "In some cities Digital Diaspora Family Reunion is leading the charge and other places Through a Lens Darkly is booked first and then Digital Diaspora Family Reunion is brought in," says Harris. He is currently talking with partners and sponsors, and he anticipates big news for the future of the Reunion project.

Filmmaker John Singleton became another supporter of the film. In 1992, he was the first African American, and the youngest filmmaker, to be nominated for an Academy Award for Best Director, for Boyz N in the Hood. After seeing Through a Lens Darkly, Singleton states, "I was moved by the film, these artists and what their work means to me and to the world at large. This documentary highlights the ongoing battle that black people face defining themselves image-wise." After the film debuted at the Sundance Film Festival, Singleton signed on as executive producer. "It's been amazing having John Singleton on board," Harris exclaims. "He's helped with opening certain doors and has been a consul of support, helping to strategize with placing the film."

At the Berlin International Film Festival earlier this year, Through a Lens Darkly was well received by German audiences. Two days after that screening, Karen Cooper, head of Film Forum in New York, booked the film for two weeks, beginning August 27. The film is distributed through First Run Features and will continue to travel to Chicago, Milwaukee, Columbus, New Orleans, San Francisco, St. Louis, Los Angeles and Baltimore.

Tracie Lewis is a writer, producer and beginning photographer.

'Big Men' Director Rachel Boynton on the Complex World of Petro-Politics

Filmmaker Rachel Boynton takes on a monolith of a subject in her documentary Big Men, submerging herself in the world of the oil industry as Kosmos Energy, a US-based oil company, discovers an oil field off the coast of Ghana—the first such discovery in that country's history. Suddenly, the question "Who gets what?" is on everyone's mind and the vying for the resource begins. In an analogous situation in Nigeria, the discovery of oil in 1956 has, over the past several years, left many communities in a mercurial lurch and oil companies unsure of pipe security. Boynton is determined to find out if Ghana would endure the same fate as Nigeria.

Viewers looking for an oil documentary with clear heroes and villains will be disappointed; Boynton does not judge her subjects, but shows their stories and characters as they are, doing justice to the multifaceted, complex and undeniably human conflict. She takes viewers on an expedition into rare territory for documentaries, interviewing everyone from militants in Nigeria to oil executives, politicians and activists to everyday citizens. Big Men is, at its heart, a story about capitalism and human nature. While those with means have a viable shot at profiting from Ghana's oil, what happens to those who receive the short end of economic inequality?

Documentary caught up with Boynton over the phone, and we discussed her research, the backup story that never aired, and the challenges she faced and the insights she gained during her eight-year journey of making Big Men.

Documentary:What was your research process for Big Men? Where did the idea for the film come from and where did you begin in your research?

Rachel Boynton: I finished a film called Our Brand Is Crisis back in 2005, and I started thinking about what I wanted to do next. At the time, oil prices were steadily climbing. In 2006, every five minutes on CNN there was something about the price of oil and how we were all going to hell in a hand basket, because we were running out of the stuff.

I've been interested in films that look at big ideas about how the world is today. And I thought the oil industry was ripe for a great documentary, because I've never seen anything about the oil business from inside the business. There are reasons for that. It's very hard to get into the oil business to make a movie, which I discovered as I went into it.

I started doing some research and I realized that the coast of West Africa was considered this new frontier for a lot of oil companies. I thought that could be an interesting setting for a film—deepwater exploration in particular.

Right around the end of 2005, there was this militancy that started popping up in the news out of Nigeria. Groups of young men were attacking pipelines, kidnapping oil workers and demanding more money for their region. Their attacks were causing world-wide oil prices to peak.

I thought that that would be a great backdrop for trying to find the right story. So I decided I would go to Nigeria and try to get access to an American oil company operating there. That was the original concept for the film.

I started in 2006, and spent a year and half travelling back and forth, particularly to Nigeria. That's where most of my research took place. I was trying to meet the people I needed to meet in order to guarantee our safety during the trip and get access to all the various people in the film. It took a lot of work because I didn't know anyone when this started.

D: In Big Men, you were able to access a wide range of entities that are seemingly off-limits, from a board meeting at The Blackstone Group to the jungle headquarters of a militant group. In a previous interview you said you gained access to Kosmos Energy with a Powerpoint, but how were you able to get access to other groups such as the militants? How did you find the people to put you in connection with them?

RB: It's important when you're doing something like this, that you have money to finance the initial trips. I spent, like I said, a year and a half travelling back and forth with no movie; I wasn't in production. I could never have made this film if I hadn't spent a year and a half doing nothing but walking around talking to people.

I met a guy in Nigeria who was basically my patron saint. He worked for an oil services company there and he allowed me to live in his guest bedroom.

That's hurdle number one: the money. Hurdle number two is, How do you go about meeting people you need to meet—especially when they're from such disparate worlds? I have a basic theory about that: the six degrees of separation theory. Everyone is connected to everybody else, especially when you're operating in what is essentially a very small world. The oil executives are connected to government heads, who are connected to the militant leaders. You're not going at it trying to get directly to the person you want to get to; you're going at it trying to get into the world of that person. And a big part of my initial work, particularly when it came to the oil world, was really about meeting people—any people—in the world of oil exploration and convincing them that I wasn't some scary, liberal-minded documentary filmmaker who was going to come in and trash the scene. I had a lot of work to do to convince them that I was interested in actually listening to what they had to say. And a lot of that was about forming relationships.

When I got on that first plane to Lagos, I had a few phone numbers and one of them was my husband's business partner's brother, who had gone to high school—boarding school—with a guy who was Nigerian. He was the guy who helped me get my first hotel room and basically arranged for a guy to pick me up from the airport, so I wasn't entirely by myself when I arrived. And he ultimately worked on a political campaign in the Niger Delta during an election cycle there. During that political campaign, because politics are very connected to the militancy—or at least were at the time—he met the wife of a very important militant leader. He introduced me to her, she introduced me to somebody else, who ultimately introduced me to the person I needed to know.

Militants in Delta State, Nigeria. Photo: Jonathan Furmanski

You spend an enormous amount of time doing nothing, feeling incredibly frustrated and wishing you could be more productive. And if somebody says "No" to you, you come back and try again several months later. You have to have a vision in your mind that you're going to get it done. If one thing doesn't work, you have to figure out something else worth trying.

D: Was there anything you learned before production and during production that really surprised you?

RB: The thing I always go back to is, having spent as much time running around Nigeria as I did and then coming back to New York City—the two places couldn't be more different. That experience really ingrained in my mind a sense of my own privilege in a way that nothing else in my life really has. How many things in my world actually do work; how much the world can go awry and be impossibly difficult for people who live in circumstances where their society doesn't function like our society; how divided the world is by economic opportunity—those things you know intellectually, but it's very different to walk out into the world and get your feet in the muck of it and see what it is.

I think this all made me a lot more humble just as a person. It taught me how much I don't really know about the world.

D: Did you go in with any expectations for how things would turn out or how you would feel about your interviewees?

RB: I'm married to a fiction filmmaker. We spend a lot of time watching fiction and talking about scripts and analyzing story structure and things like that. Both Our Brand Is Crisis and Big Men have very traditional narrative structures in terms of a climax, a resolution and characters who go through something. The thing is, because it's reality, you don't know what the story's going to be when you're launching yourself into it. What you can do is pick circumstances that you think will result in a good story. In order to do that, you need to pick a circumstance where you know there's going to be conflict. And it was a pretty easy bet to say that in the development in the country's first oil field, somewhere in that scene, there's going to be conflict. This question of who's going to get what is there from the very beginning, even if everyone is acting super happy about what they've found.

I very purposely picked a subject matter that I thought would generate a narrative story structure. In Our Brand Is Crisis, I picked a campaign. There was no campaign [in Big Men], but I always knew I was going to try to follow the story arc through first oil and see what happened over the course of time.

Now, I had a backup plan. It could have happened that I followed Kosmos through first oil, everything was hunky dory, nothing went wrong—and then there would have been no conflict. So I had another story that I actually filmed that didn't make the movie. I filmed with the US Navy, in both Ghana and Nigeria as they were training local forces to better protect the oil wells off the coast. And if I had to, I could have constructed a film that was about more internationally oriented ideas rather than these micro-economic ideas, about what's happening to a particular company in this particular place.

D: Have you wanted to release that story?

RB: No, I want to move on with my life. I worked on this film for seven to eight years. I'm very ready to be done.

D: Did any of your interviewees have second thoughts about being in the film or the information they shared with you?

RB: I don't know. I think anyone who agrees to be in a film is interested in being acknowledged and seen. So I think the response to the movie often has to do with if they feel that they've been portrayed as they are and if they have the self-confidence to confront that and be okay with it. And the people in this film, like the oil guys, have all been really happy with the film; I think they feel like it presents them as they are. I showed it in Ghana and the one person who wasn't happy with the film was the Minister of Energy. He was not somebody I expected to be unhappy; I thought he came off quite well. But that just shows you that you can never really predict who's going to like something and who isn't.

D: Do you continue to stay in contact with any of your interviewees?

RB: I've been in contact with all the oil guys and the financial guys. [Venture capitalist] Jeffrey Harris is in New York, so I've seen him at several screenings. And I've been in touch with the guy from Ghana. I have not been in touch with the militants. For a long time I thought I was going to go to Nigeria and specifically show the movie to them, but I had such a complicated, difficult experience going to Ghana to show the film, that I decided that frankly, I didn't want to put myself in that position.

Filmmaker Rachel Boynton in Delta State, Nigeria. Photo: Jonathan Furmanski

D: What made it difficult to show the film in Ghana?

RB: Well, I'm a white girl from New York City and I'm coming into a place and making a story of what I see. So Big Men is going to inherently have my perspective; it's not a Ghanaian perspective. I wish there were more African documentary filmmakers who were empowered and financed to go out and make big movies, because the world needs that and I imagine it's probably a pretty frustrating thing to look at your story as told by somebody who's not from your place, an outsider.

The majority of the Ghanaians who saw the film really liked it and appreciated it. The people who had trouble with it had very politicized or particular views of the situation, and didn't perceive the film as balanced. They perceived it as being pro oil company. That was never my intention and I don't see the film like that at all. There's not a tradition in Ghana of storytelling that tells both sides. There's more of a tradition of storytelling that tells one side. So if you include both sides, then both sides kind of say, You shouldn't be telling the other guy's side, and why are you doing that? So there's not the same space necessarily for different kinds of storytelling. But I was quite surprised that the Minister of Energy was as upset as he was, because I think he comes across in the film as a guy who keeps saying over and over, "I'm not doing this for myself, I'm doing this for the country. And what's wrong with trying to get a better deal if we're doing it for our people?"

D: What do you want viewers to take away from this film?

RB: For me, it's a film about capitalism. I grew up in time when there wasn't a whole lot of questioning of the system, in the sense that it was still the Cold War era and to question the basic outcomes of capitalism, they'd think you were a Red. And over the course of my life, I feel like—and maybe it's just my perspective has changed—but the income disparity I see in America and the world, I find very disturbing. And the concentration of enormous amount of wealth in the hands of a very few, I find very disturbing. I have no criticism of individuals who are in that world; I think a lot of them do great things with the money they make. But for me, questioning the essential values of the system is one of the big points of the movie.

But you want it to be a great movie with an exciting story that takes you into crazy worlds that you've never been in before. You want to have the thrill of the access to the militants, to the oil executives. You don't want it to be some polemic.

My hope for the film is that it will persist and that over time it will engage people and get them thinking. It really is fundamentally a film about capitalism and about how our world works—not in a way that's judging the characters of the film, not in a way that's looking at one group of people as good or bad, but it is posing an important question about the justice of that pursuit and what it entails and what it means for everybody involved in the film.

Big Men airs August 25 on PBS' POV.

Corinne Gaston is a writer, editor, activist and researcher originally from Pennsylvania. She is currently the deputy opinion editor of Neon Tommy and is finishing a degree in creative writing at USC.

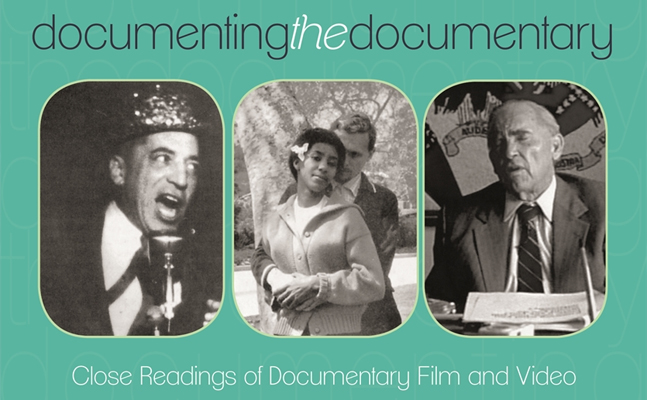

Documenting the Documentary: Close Readings of Documentary Film and Video

New and Expanded Edition

Edited by Barry Keith Grant and Jeannette Sloniowski, with a Foreword by Bill Nichols

Published by Wayne State University Press 2014

If I was suddenly asked to teach a History of the Documentary class and told that my budget would allow for the use of just one textbook, Documenting the Documentary: Close Readings of Documentary Film and Video is the one I would select. The first edition was released in 1998, still a time when documentary was elbowing its way into film-school curricula. This new anthology includes all the previous, exemplary essays as well as five new entries covering more recent films, bringing the discussion and analysis of the most influential examples of the genre up to date. Each essay is followed by notes and works cited, making for a very handy, useful way of organizing the material. Brief bios of all the contributors—some of with whom I was familiar, while others were welcome discoveries—are listed in the endnotes.

In the Foreword, Bill Nichols, the highly regarded documentary scholar and theoretician, tells us, "The complex, fuzzy boundary to the enterprise of documentary filmmaking is well registered in the striking absence from the first quarter-century of cinema (roughly 1895-1922) of any single word for what we now call documentary." This reinforces the knowledge that the genre is still a youthful enterprise, growing and evolving towards a more mature state, but a maturity whose form is not written in stone. A bit later he adds, "It remains to this day, a practice without clear boundaries." Perhaps it is this idea that continues to make documentary so exciting to makers as well as students of the form—the lure that if we engage, we can push the envelope and explore the landscape, and in the act of doing so, new realities will be revealed.

The book weighs in at a hefty 570 pages and is roughly chronological, beginning with "The Filmmaker as Hunter," William Rothman's familiar analysis of Robert Flaherty's Nanook of the North (1922). While a statement on the video release prefaces the film by saying, "This is generally regarded as the work from which all subsequent efforts to bring real life to the screen have stemmed," Rothman points out that while Nanook of the North "accurately illustrates aspects of its protagonist's way of life, its primary goal is not to contribute to a body of scientific knowledge of human cultures; it is far from an ethnographic film in the current sense." So already we can see, right from the start, that this thing we have designated as "documentary" will be a contested arena.

We are reminded in the introduction that in 1998, when the first edition of Documenting the Documentary was published, Michael Moore's Roger and Me (1989) had been "the most commercially successful documentary of all time." Since then, many documentaries have surpassed that benchmark, including four from Moore: Fahrenheit 9/11 (2004), Sicko (2007), Bowling for Columbine (2002) and Capitalism: A Love Story (2009). Interest in the documentary form had been rising in 1998, and the trajectory of this interest has only changed in that it is more ubiquitous than ever. We have become a world of documentary makers; we are openly and furtively capturing our own lives as we live them, one cell phone and YouTube upload at a time.

There is a broad misconception that documentaries are inherently more truthful than other films. They are not. We are assisted in unraveling this conundrum—what is real and what is true—when we examine a film like Dziga Vertov's Man with a Movie Camera (1929). In this chapter by Seth Feldman, "Peace Between Man and Machine," I found some of the most potent revelations regarding documentary film's power to both embody and predict the future. In the film's famous logo, a human eye superimposed on the camera lens, we see the perfect melding of human and machine-a forerunner of an increasingly blurred line between living flesh and inert material, as we absorb more machine parts into our bionic bodies, helping us to survive catastrophes in ways that Vertov had only begun to imagine in 1929.

Although his hoped-for "peace between man and machine" seems further away than ever, other ideas, then visionary, have become our new reality. Fed by the atmosphere of a rare period in Soviet history of social and economic pragmatism and artistic tolerance, Vertov proposed that Soviet films be "shot by large numbers of ordinary citizens acting as film scouts, edited collectively and exchanged in a vast nationwide network." It's as though he predicted our Googlized, Wikipedia'd and YouTubed culture 35 years before Marshall McLuhan declared that media is the "extension of man." There was a revival of interest in Vertov's work in the 1960s, and his work has even greater ramifications today.

We move from Vertov to another Soviet filmmaker, Sergei Eisenstein. Joanne Hershfield brings her in-depth knowledge and focus on Mexican cinema to an analysis as ethnography of Eisentein's Que Viva Mexico! (1932). Ethnographic filmmaking is an interesting and influential sub-genre of the documentary form that reached its zenith in the 1960s and '70s but had not yet been recognized as a scientific form in the 1930s when Eisenstein first came to Mexico. Hershfield's investigation of the filmmaker's encounter with the anthropological "Other" in Que Viva Mexico! makes for a richer understanding of the meaning of ethnographic film.

There are 31 essays in the book. The last two—"You Must Never Listen to This: Lessons on Sound, Cinema and Mortality from Werner Herzog's Grizzly Man" by David T. Johnson and "Cultural Learnings of Borat for Make Benefit Glorious Study of Documentary" by Leshu Torchin, bring us into developments in documentary of the last decade. Herzog, perhaps more than any other documentary filmmaker, makes good use of that fuzzy boundary between truth and fiction to achieve what he refers to as "ecstatic truth." He is notoriously ambivalent about subscribing to the terms "documentary" and "narrative" in defining his own work, and he relies on a "poetics of truth" to reach what is perhaps a more intense experience of reality. Sound—its presence and absence—is key in dissecting the aesthetics of Grizzly Man. For Johnson, this is apropos, as the theory and history of film sound has been central to his academic interests.

In the Borat essay, the term mockumentary surfaces for the first time in these discussions and, as Torchin points out, "begins to help us understand the work of the film, but it fails to account for the elements of cinema vérité, the reportorial truth-claims, the clear documentary potential of Borat's interviews." It is as though we are on a teeter-totter, slipping and sliding, up and down, between documentary and fictional elements, as allusive to the characters in the film as they are to the audience. As Borat traipses across the country, we are left to ponder who we are as Americans and what we really know about ourselves.

As we become ever more besotted by filmed "reality" delivered to us on our handheld devices wherever we are, whenever we want it, we need to be reminded, through a thorough review of the history of the genre, how all this happened so we can bring a critical awareness to what we view as a consumer and what we set out to create as artists and craftspeople. With this book as our guide, we will come out at the end of this exploration with "a profound appreciation of the aesthetic complexity of the documentary form."

Cynthia Close is the former president of Documentary Educational Resources and currently resides in Burlington, Vermont, where she consults on the business of film and serves on the advisory board of the Vermont International Film Festival.

The Storyhunter team in their Brooklyn office, reviewing pitches from around the world. Courtesy of Storyhunter

The Botanic Lab Bar on Manhattan's Lower East Side bustled with the energy of a typical Friday night crowd. International filmmakers, tech leaders and producers all gathered together in the relaxed vibe of the basement lounge, sipping herb-infused cocktails and listening to the ambient, pulsating beats of a world-music mix perfectly suited to the laid-back atmosphere of the room. At first glance, it appeared to be not unlike any other scene with an underground buzz and a focus on eclectic mixology.

The one exception, though, was the big projection screen propped next to the DJ booth, playing a documentary short about the new recreational skiing scene in Bamiyan, Afghanistan. Less meat market and more creative nexus, this Friday night was different in that it played host to Storyhunter's second anniversary bash, a networking event for the video journalism start-up.

Storyhunter, the brainchild of co-founder Jaron Gilinsky, came to be as a premier network for video news journalists and documentary filmmakers to pitch unique stories and increase connectivity between artists and publishers. Working the freelance circuit as a video journalist himself, Gilinsky saw first-hand the inefficient, and often times corrupt, management style of international news bureaus, manifesting in a growing disconnect between filmmaking talent and distribution outlets.

"There was a pandemic in the media," says Gilinsky. "I saw how repressed journalists were." Creatively stifled, news journalists often fell victim to political propaganda, forced to comply with the regulations of government-controlled networks and cost-cutting foreign bureaus. One of Gilinsky's colleagues left a job at a main Nepali news station after refusing to submit to a controlling political hand. "There weren't any real creative news jobs in town," says Gilinsky. "There was no way to book a gig."

Cut to 2011. With a mounting frustration in the lack of creative control for video news journalists, Gilinsky stumbled upon his greatest source of inspiration in the then-emerging Internet networking service known as AirBnb. Now wildly successful, AirBnb initially based its business model on a simple exchange of need and want, targeting young, travel-centric Millennials looking for cool, affordable housing options. "I saw what AirBnb was doing, and I knew this was the new way," says Gilinsky. "Creating a need and building a platform based around that demand was exactly what I wanted to do for our industry." After raising funds and partnering with co-founder Alex Ragir, Gilinsky launched Storyhunter in May 2012, establishing a database for trusted, talented filmmakers to connect with publishers and distributors in need of creative, forward-thinking news content.

The business model for Storyhunter is simple. Any video journalist or documentary filmmaker can fill out a form requesting a short bio, examples of relevant work experience and links to online portfolios. From that point, the Storyhunter team begins a strategic vetting process.

"My main focus is to build a trusted network," says Gilinsky. "We need to feel confident that filmmakers aren't going to manipulate the truth, since we're handing them to publishers who trust us." Once a filmmaker has been given the seal of approval, he or she is welcome to post pitches for assignments already listed in the database, or he or she can send an open pitch for any original story. All items are tagged in the database, so it's easy for those in the network to search ideas related to their expertise. "It's great because instead of one long e-mail chain, hundreds and thousands of editors and publishers can pick your story pitch," Gilinsky notes. Much like the AirBnb model, Storyhunter fosters a credible, symbiotic relationship between creative talent and publishing outlets.

In fact, the network has progressed so steadily over the last two years that Gilinsky and Ragir have been able to launch hugely successful licensing deals with AOL, Yahoo and PBS, providing more and more opportunities for video journalists to create a variety of unique, documentary-style news stories. In 2013, Storyhunter partnered with AOL On, an online news channel featuring exclusive Storyhunter content. Shortly thereafter, Gilinsky finalized partnerships with several of Yahoo's international markets, including Mexico, Columbia and Brazil, establishing a Storyhunter Channel that spotlights close to 200 original stories. It's currently one of the most popular Yahoo channels on the Web. In December, POV, the PBS documentary strand, commissioned Storyhunter to produce several online shorts to coincide with the broadcast premiere of Joe Brewster and Michèle Stephenson's American Promise. Filmmakers Noel True and Rob King, the husband-and-wife team behind the LA-based production company Little Pictures, saw the call for pitches and decided to give it a go.

The pitch, which asked filmmakers to submit story ideas about the achievements and challenges facing young males in today's African-American communities, piqued the interest of the LA duo, since their aesthetic fell perfectly in line with what POV was looking to produce. "We knew Storyhunter was based more in video journalism, while we work more in a documentary style, creating character development and story lines," True notes. "However, Storyhunter gave us an opportunity to knock directly on PBS' door." Their original piece, titled The Jazz Ticket, told the tale of Vince Womack, a high school jazz teacher helping students from rough Los Angeles neighborhoods find a means to college through music education. The film was ultimately chosen as one of the three POV-commissioned shorts, and it even won them the Storyhunter of the Month award in January of this year.

"Because of our success with POV, we've now been accepted into the Storyhunter network," True says. "We've been vetted, which is great." The Little Pictures duo, who currently produce documentary shorts for corporate clients, were more than pleased with Storyhunter's flexible approach to filmmaking, providing a comfortable environment for the creative process. "They gave us enough rope to create a journalistic piece while still allowing us to maintain our documentary aesthetic."

Similarly, the Fusion network, a joint venture between ABC and Univision, commissioned Storyhunter filmmaker Carlos Beltran to produce several pieces from Caracas, Venezuela, documenting the riots and student protests that took place in February of this year. "I was interested in the documentary approach to news stories," Beltran maintains. "It took me in." Joining the network in 2012, Beltran has since been working seamlessly with Storyhunter from Caracas, noting the efficient responsiveness from the network team in New York as the crucial factor in establishing such a strong creative relationship. He's covered about five full news stories through Storyhunter, and he's found these specific pieces have hit a reach far beyond what he would have initially anticipated had he produced them through another venue.

And despite Storyhunter's notable achievements over the two short years of its existence, Gilinsky and Ragir are still concerned with the small-pond model in which the network currently exists. "Right now, we get about 5,000 pitches, and about 350 of them are picked for production," Gilinsky explains. "I'd like to increase that number." Innovation, speed and responsiveness appear to be Storyhunter's approaches to success, and with the growing popularity of the video news medium, the network is positioned nicely to enhance its visibility within the market.

Jane Dubzinski is a freelance writer based in Los Angeles. She has an MA in English Literature from Cal State LA and hopes to pursue a PhD in cultural studies. She also loves the Boston Red Sox.

Every Picture Tells a Story: Jeremiah Zagar Revisits 'The Trials of Pamela Smart'

As documentary filmmakers, we use images to help us tell stories. We chop up things that people say to "help them" say it more clearly, often masking the sound cuts by sticking them underneath some nice archival footage. Archival footage has been used in documentaries almost as long as there have been documentaries.

But storytelling has evolved. In the last couple of years I have seen a wave of documentaries that use archival footage in order to comment on its meaning as much as its use in service of the story. In Captivated: The Trials of Pamela Smart, about the New Hampshire woman whose televised murder trial and conviction in the early 1990s ushered in a decade of media-stoked courtroom sensations, archival footage is as much a character in the film as Smart or her accusers. Her trial was the first ever to be aired on live TV, and it inspired a raft of books and films, so Pamela Smart-related footage is in abundance.

We talked with director Jeremiah Zagar about the story, the process and these issues.

Pamela Smart entering the courtroom, 1991. Courtesy of Public Record

Documentary: How did you come to tell this story, and what did you know about it before you went down the rabbit hole?

Jeremiah Zagar: I knew nothing. Lori Cheatle, the producer, had seen my film In a Dream. At the time, I was working as an editor, cutting a lot of trailers. She asked me to cut the fundraising trailer [for Captivated], and in the process I saw the archive she had amassed, and it was incredible. I fell in love with the material, and she asked me to direct and from there the rabbit hole opened up. Lori brought me on and started raising money for shooting initial interviews. Then HBO, Lisa Heller and Sheila Nevins came on board, along with Passion Pictures and Sky Atlantic, and four years later, here we are.

I was reading all these Janet Malcolm books at the time and the ethos of the movie became "Janet Malcolm Meets 12 Angry Men." Janet is a journalist, and in her work she examines the relationship of journalists to the accused and to the trial. She also examines the relationship of each player to the trial process: how trials are constructed, and how trials are a mirror to our storytelling process. Thinking about the Pamela Smart case in this way really started to interest me.

D: The film seems to be as much about media, memory and culture as it is about Pamela Smart. How did you weave these threads together?

JZ: There had been a million Pamela Smart movies before this, so we had to look at this differently.

When I began the film, my friend [the late photojournalist] Tim Hetherington said, "You need to look where everybody's not looking." And no one was looking at the lookers. Often the people watching are so much more interesting than those being watched. The phenomenon that is our justice system is in many ways much more interesting than this case. In this instance it's a he said/she said situation. There's no way to prove what really happened, and the whole thing aired live on TV. It's in the ether, something we are all complicit in—the reason Pam Smart is spending so much time in prison is due to this process of media-watching, media-buying and media-creation.

As we began to do the interviews, our editor, Keiko Deguchi, and I began to cut the footage together. We don't do the normal doc process of shoot and then edit. We shoot a little, then edit a little, then shoot a little. We build the structure as we edit. The edit informed the interviews, and vice versa. Therefore the questions we asked began to be dictated by what we knew the movie would become.

Pamela Smart today. Courtesy of HBO

D: It was a matter of both timing and perspective—and how we almost had to wait 20 years to be able to understand what took place.

I think right now we're a little outside the bubble of that time frame. It's becoming clear to people that the sentence was insane. At the time, society had turned Pam into a disease. It was a great way to demonize her, to say that her degenerate moral fiber might affect the children. It was good way to put someone away forever. It's important to ask, "How did this happen?"

I think that the tapes that the juror recorded in the trial were essential in terms of giving us perspective. I'm not a true crime person, but every time I would put on the trial tape, I could feel myself leaning in. I wanted to know more because trials are innately fascinating. They are structured as stories. Why is that? Rather than re-tell the story of this trial, the goal became to examine the idea of storytelling in a trial. In order to do that, we had to retrace the trial.

D: In terms of aesthetics, can you talk about your approach to working with the archival and the more recent interviews?

JZ: As an editor trying to figure out why stories work and how we communicate, I'm interested in devices of storytelling, and tropes and patterns. I became fascinated with true crime and why people consume it at such a high rate.

Archival often lays flat on the screen, and it doesn't feel part of an integrated cinematic environment. We wanted to put the audience in the position of watching as if they were there. So we put every piece of archival on a TV and with Naiti Gámez, our DP, we shot in a locations where people might have been watching it at the time. On top of that, Gabriel Sedgwick, one of our producers, found a guy who had created a transparent screen for projection in storefronts. We built this screen and we'd bring it where we went to do interviews. We would show our subject the archival footage projected in front of his face, so that we could see their reaction to it. I did something similar to this when I made a film about my father, In a Dream. We couldn't see the footage, but seeing my father's reactions made the film.

In this case, you get to see the footage and the reaction. That's important in terms of what we were trying to raise questions about: Who were these people, and how they were changed by viewing this media?

An interviewee with footage. Courtesy of Public Record

Captivated: The Trials of Pamela Smart airs August 18 on HBO.

Michael Galinsky is partners with Suki Hawley and David Bellinson in the award-winning production studio Rumur. Their film Who Took Johnny premiered at Slamdance. They are currently working on a film about the connection between stress and pain.

Hollywood likes to tell stories about itself. But like the movies it makes, it often sacrifices reality for a good story. One such story goes something like this: In the late 1960s, the studios had lost direction and weren't in touch with the new generation of moviegoers. In this confusion, a group of young rebel directors were given free reign to turn out a slew of films that would change cinema forever. When they name these rebels, they typically include Francis Coppola, Martin Scorsese, William Friedkin, Peter Bogdanovich and Robert Altman. What many don't realize is that Altman was at least a decade older than those others. Altman had a long career directing episodic television before he burned that bridge over then-sponsor Kraft's refusal to let him cast a black character in an episode of Kraft Suspense Theater. He declared the program "as bland as their cheese" and for the next couple of years he couldn't get any television work, so he decided to make feature films. Altman was always an iconoclast, and a film made about him, according to director Ron Mann, had to reflect his impertinent spirit.

"I could have done a life and times, American Masters, typical television-style, commercial film," Mann says of his homage to Altman, simply entitled Altman. "But how could I make a conventional film about an unconventional filmmaker? It's what I've been pretty much against throughout my own career."

What Mann (Comic Book Confidential, Grass) decided to do, as opposed to what he considers to be a "conventional" documentary—which he goes on to describe as "interviews with insiders who tell war stories, and illustrations"—was to let Altman, who passed away in 2006, speak his own words from beyond the grave: "It was more intimate to have Bob in his own words tell his own story." And he blends Altman's voice with home movies, photographs, behind-the-scenes footage, film clips and on-camera interviews with him.

That is not to say Altman is the only voice one hears in the film. There's Altman's wife Kathryn and his kids who contribute to the picture Mann paints. And there's a handful of others, such as members of Altman's loosely-defined "stock company," including Lily Tomlin, Keith Carradine, Sally Kellerman and Elliott Gould. Those actors are not there to "tell war stories," however, but are all asked the same single question: "What is your definition of 'Altmanesque'?"

Robert Altman on the set of his 1993 film Short Cuts. Photo: Joyce Randolph. Courtesy of Epix

"Even the actors and the people I interviewed were surprised that I only wanted to ask them one question," Mann says. "You really don't get a sense of the person in the conventional documentary. I could have adapted, for example, Mitchell Zuckoff's book, which is a very [journalist George] Plimpton-esque oral history of Bob, which inspired the project in the very beginning. But I went to the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, where Bob had gifted his archive, and he left a trail for me to follow."

That trail, as Mann notes, he found in Altman's archives. "Bob had kept a record of all the interviews he had done over his career, and so I was able to track them down. It's amazing that he left us such an audio-visual record of his life, which allowed me to make a film in his voice. Most documentaries don't have access to the source.

"I'm not really a spiritual person," Mann continues. "But I sort of felt like I wasn't in control of this movie. It was almost like I was channeling Bob. 'What would he do?' I kept asking. It just sort of fell together in this kind of organic way."

Although they never met, Mann grew up with a deep appreciation of Altman and his films. He even wrote a paper in college on 3 Women and Images. "For me, he was America's greatest director," Mann asserts. "Bob's work is completely of its time. Bob was a naturalist. He was after human behavior and he portrayed things as they really are. Maybe that's why as a documentary filmmaker, I have that affection for him. He was someone who was technically innovative. He changed the way sound was recorded, the way the camera moved. He was older than the other counter-cultural directors, but he had this independent streak and definitely thought like a young person. I mean, here's a guy who made a short film about pot in 1965. Bob was really prescient, leading us to where we were going. He also reflected what he saw and made people look through his window. As a whole his work stands out as a portrait of America of the late 20th century."

Robert Altman (right) on the set of his 1977 film 3 Women. Courtesy of Sandcastle 5 and Epix

Mann began the project two years ago, and recalls, "When I first met Kathryn [Altman], she said, 'What do you want to do?' And I said, 'I have no idea. How do you scale a mountain?' But one thing I told Kathryn in the very beginning when she gave me permission to make this film was, 'I am not going to fuck up.' And that promise to Kathryn was what kept me up nights for two years. And when I showed it to her, she just went through a box of tissues while she watched it. And she thanked me, saying I really captured Bob—his playfulness, especially. To me, that was the most important thing, more than any reviews or what anyone could ever say. When you're representing someone else's art, there's a tremendous responsibility that's given to you, and she trusted me."

Unfortunately, Mann says, "The US broadcaster, Epix, was appalled" when he showed them the film. "They were upset with me because I wasn't giving them a television documentary. Epix looked at my cut and said, 'Ron, you have to hire a story editor.' And I said, 'What?!?' Look, I'm a nice guy and they gave some money, so I thought, 'Okay.' I went through their list of suggested story editors and on this list was a guy and I called him. He comes in and looks at the cut of the film and says, 'Don't touch a frame of this.' And this was their approved story editor." So with that and the family's approval, Mann's film was left alone.

Both Mann and Altman have made films covering similar territory: comic books, marijuana, jazz and the food industry. "I don't want to stretch it," he says, "but I never thought of how he and I have covered a lot of the same territory. I make films about my heroes, people who I've felt are important to give recognition to and to amplify their work. So I connect with Bob on many levels."

When asked what he discovered about Altman he hadn't been aware of previously, Mann responds, "Kathryn. It takes a very special person to be married to a filmmaker and he was very fortunate to have found that very special person."