On August 20, 2013, with a click of the remote, American households were able to get their news and commentary from a new venue: Al Jazeera America. Starting a new channel in an already overcrowded cable news scene seemed risky, but the high quality programming soon silenced the naysayers. The day it launched, Al Jazeera America aired Fault Lines: Made in Bangladesh, about American retailers turning a blind eye to the dangerous practices of overseas subcontractors. The following day came Fault Lines: Haiti in a Time of Cholera, which examined the post-earthquake epidemic that decimated the survivors. Both of those episodes won Peabody Awards this year.

With a number of groundbreaking documentary series airing, and more in the pipeline, the channel is rapidly becoming known for documentaries that look at issues in a novel way. Borderland, a four-part series on immigration from executive producers Ivan O'Mahoney and Nial Fulton, profiles six people with disparate views on immigration, as they follow the tragic journey of three immigrants—one of whom was a 13-year-old boy—who died trying to cross the border. The System features veteran filmmaker Joe Berlinger (Brother's Keeper; Paradise Lost) as a guide through the problems of the justice system, each episode examining a distinct issue: faulty forsenics, false confessions, flawed eye-witness testimony and mandatory minimum sentences, to name a few.

Documentary spoke to Shannon High-Bassalik, senior vice president for shows and documentaries, about Al Jazeera America's mission and goals, and how it differs from other channels that air docs.

What is the programming culture and philosophy of Al Jazeera America?

Shannon High-Bassalik: Documentaries are in the DNA of Al Jazeera Networks as a company, so when they created Al Jazeera America, it just made sense to them to have a very high and prominent role for documentaries in the US. Our philosophy is telling rich, compelling stories from regular people's point of view. We're not into the politician's or the pundit's spin; we really are about immersive storytelling—stories where you learn something but also feel something, and walk away at the end feeling that you know more and understand more because you've seen it from that person's perspective.

What is an Al Jazeera documentary? How does an Al Jazeera documentary differ from one on POV, or Independent Lens, CNN Films or HBO?

I actually think we're going to be very distinctive in this way, because we're really looking for films that are immersive and experiential. Borderland is a really good example of that. We wanted to tackle the topic of immigration because it's really divisive. It's been done many times before, but it's been done in a pretty traditional way.

This documentary doesn't have a point of view, which is important because we don't come to things with a point of view at Al Jazeera. We let you see things from the ranchers' point of view and the problems they face, to immigration and border patrol officers, to the immigrants themselves. So by having viewers walk in the shoes of the ranchers, border patrol and immigrants, you come out of the four-part series really understanding it, no matter your point of view; whether you are pro- or anti-immigration, you understand why we have the problems we have.

And we're hoping that leads to a conversation about immigration because that's really what Al Jazeera is about: We want to generate a conversation on all topics. That's how we're really going to stand out-we're really looking for more immersive and experiential kinds of documentaries.

In terms of formats, you have a mix of one-offs, such as Holy Money, and series such as Borderland, The System and Edge of Eighteen. Are you also open to shorts?

Yes, I have a magazine program called America Tonight, and I also have a half-hour documentary film show called Fault Lines. So when I'm approached with those types of films, I will connect those, depending on the topic. And I wish I would get more of those, frankly, because I would love to populate them in my America Tonight magazine program.

How do you find your films? Do you mostly commission films, or do you pick up completed films as acquisitions at festivals? How are filmmakers approaching you—in pitching forums or independently? Do you accept unsolicited pitches?

All of the above. I have a terrific documentary unit that is very experienced, is fabulous in acquisitions, goes to all the festivals, and is very in tune with that filmmaker community. I have team members who come from channels and are used to getting pitches from production companies. And at least half a dozen times a day, I will get an email from somebody who wants to pitch me a doc or a series. We're pretty much inundated.

How do you work with the filmmakers?

We're very organic. While we want them to fit into our mission of immersive storytelling and stories from the people's perspective, we're open to both the topic and how it's done. Our three series [Borderland, The System, Edge of Eighteen] are very different. Borderland is very experiential; The System is very investigative—not your typical justice system story. It's Joe Berlinger confronting government officials. And for Edge of Eighteen, coming in the fall and produced by Alex Gibney, we recruited 15 high school students from around the country with really interesting, unique stories. They got training from Gibney and other top documentary filmmakers like Alexandra Pelosi, for a week in New York. And they are filming their stories about what it's like to be a senior in high school and a teenager in the new millennium.

These are examples of series that address issues that are important to us: immigration, the justice system and education. When we look at films, we look at the issue and how they are coming at this issue. Is it a creative way? Is it immersive? Is it experiential?

We're not your father's documentary; that really does sum up some of the films, even the acquisitions and the commissions, the one-offs, that we are looking at and have purchased.

Should filmmakers come to the table with a multi-platform trans-media strategy, or is that something you develop in house?

It depends. Edge of Eighteen came to us with a multi-platform pitch, but no, not always. But it is something we develop because a multi-platform presence is important to us. We work with filmmakers and come up with a plan.

Is there a different programming strategy with respect to the website and YouTube channel?

At the moment we aren't allowed to place our docs there to be viewed in their entirety; we can place a few minutes of them. With Edge of Eighteen, for example, three of the 15 stories will actually live online. Over the course of six weeks, three to six minutes of daily footage will be shown online. Instead of being part of the hour-long doc on Sunday nights, these stories will be told exclusively online.

What is your target demographic?

We are reaching young people. It's interesting to see how young our audience is. For our coverage of President Obama's State of the Union address, our average age was 33 years old. We are skewing younger than the other cable networks. We're really targeting the Al Jazeera brand, which is the people who don't get to see themselves on television; we're talking about being a "voice for the voiceless."

Given that Al Jazeera America launched in August 2013, what have been the challenges in building an audience and establishing the brand?

A start-up is a start-up. When MSNBC and Fox News started, they faced the same challenges we face: You have to get people to the channel; they have to find you. We have a harder challenge than they did; when they launched, there was only CNN. When we launched, we were up against CNN, MSNBC, Fox, BBC, CCTV and RTV. There are so many more choices out there now for different kinds of news. So we face the challenges of any start-up in that we have to build an audience.

But we have seen steady growth in the eight months we've been in the air. We think our doc series will help that. We think that for people who have not heard of the channel or people who may only be aware of it, the docs will be a reason to come to us and check us out. Once people see us, they really like us. They like the fact that there's no screaming, we don't have a point of view, we tell stories that other people aren't telling, and we're in-depth. We have definitely seen growth and we're excited about that.

What is the barometer for success for Al Jazeera America?

The great thing about being a start-up is that I can just throw things at the wall and see what sticks. Traditional and established channels will say to the filmmaker, "This is what I want and if you can't give it to me, I don't want it." That's not where we're at, and I don't think we will ever get like that because we are very organic and very much open to all different types of storytelling.

Ratings will come into the mix, and that is inevitable, of course, because we're a rated channel and that's part of the US network culture. But I can honestly say, that if something doesn't rate well, that doesn't necessarily reflect on the doc. There are so many things that go into ratings.

So our barometer is: Is it a good doc? Is it well told? Do we think it has a potential to win awards? When awards season comes around, did it win awards?

We were only on the air last year for four months, and both in the docs and programs unit we've already won ten awards: two Peabodys, seven National Headliner Awards—Google and the World Brain won first place—and America Tonight won a Gracie.

We want to do good quality and that's really going to be our barometer. Are we being noticed by the reviewers, by the audience, by our peers, for being the channel that has the best quality—whether it's news, programs, docs or series?

What do you pay for docs in their various formats?

Obviously, we don't talk financials. It's fine you asked because everybody asks me. What I can tell you is that it is a tough market; CNN has now gotten into the game, Netflix and Amazon are now getting into it, and they are willing to throw quite a bit of money at it. I personally don't like bidding wars. The market is tough one, but one of the things we bring to the table is that filmmakers want to work with us; they understand we're long-term. Al Jazeera Networks has been doing documentaries virtually from the day that the channel started. So filmmakers are very interested in working with us because they know we're as committed to their film as they are.

What would you say to a filmmaker interested in pitching to Al Jazeera America?

No topic is off limits. We're a news channel, so we're issue-oriented. And we care about deep issues, not frivolous ones; that's not what we're about. If you've got a film that is a great issue and comes at it in an immersive, personal, compelling way, we'd love to see it.

Darianna Cardilli is a Los Angeles-based documentary filmmaker and editor. She can be reached at www.darianna.com.

The Los Angeles Film Festival made its debut in 1995 as the Los Angeles Independent Film Festival, with screenings at the Raleigh Studios' modest screening room. The documentary representation was scant in the first few years; by 1998 the festival had commandeered the then-Laemmle Sunset 5, but that year audiences were treated to just two feature docs, one of which was Bennett Miller's first film (and sole feature-length nonfiction work to date), The Cruise, which screened at 10:00 a.m. on a Saturday. Film Independent (then IFP West) took over the festival in 2002, dropped the "Independent" from the title, and later moved the festival to Westwood Village, near UCLA. The documentary programming expanded substantially in the 2000s to include a documentary competition, along with hefty jury prizes and audience awards, and docs have proliferated nearly all the strands since then.

The 20th edition, staged in downtown LA's LA Live complex, LAFF's home since 2010, competed for attention with the opening of the World Cup on Day Two of the festival, and, on Day Three, the deciding game of the Stanley Cup finals, won by the Los Angeles Kings at its home arena, Staples Center, right next door to the Regal Cinemas. Imagine the bedlam. I did; I stayed home—and watched the game, which, I'll admit, was a real thriller. My colleague Katharine Relth, no hockey fan herself, did try to face the maddening crowd—no movies for her, either! (For her report, click here.)

But there plenty of docs to go around—22 in all. And true to LAFF's programmatic savvy, Los Angeles stories loomed large in the mix. Meet the Patels, from the Los Angeles-based brother-sister team Geeta and Ravi Patel, is a delightful, six-years-in-the-making docu-comedy about Ravi's search for a soulmate—and his struggles to reconcile the tradition-bound desires of his parents to find him a suitable Indian bride with his own Western-tinged ambivalence about honor and autonomy. With Geeta as his behind-the-camera confidante, confessor, coach and conspirator, and their camera-ready parents alternatively dismayed, droll and deferential, Ravi makes for a charmingly self-effacing protagonist. A blend of animation, home movies and vérité footage, Meet the Patels tackles many themes—cultural identity, generational differences, tradition vs. assimilation, interracial relationships—in an organic, story-driven way. The film earned the Audience Award for Best Documentary Feature.

Another LA tale, N.C. Heikin's Sound of Redemption, making its world premiere at LAFF, tells the story of the late jazz artist Frank Morgan—an epic journey indeed. He settled in Los Angeles as a teenager and, prompted both by his musician father, Stanley Morgan, and his idol Charlie Parker, Morgan rose quickly in the jazz community, gaining prominence as a prodigy. Heroin throttled his promising career, followed by a decades-long life in and out of prison. All the while, he never abandoned his art—even in prison. In his last decades of freedom—he died in 2007—Morgan released a torrent of albums to complement his work from earlier decades, and although the redemption was hard-earned, he was as revered among his jazz world peers as he was when he first caught the attention of the masters back in the 1940s.

While Morgan had a tough time staying out of San Quentin, it took a year for filmmaker Heikin to get in. She came up with the idea of staging a concert there, featuring Morgan's contemporaries, such as Ron Carter, and up-and-comers, such as saxophonist Grace Kelly, but it was one of her producers, James Egan, who led the negotiation process. And that concert serves as an effective narrative spine for the film, in addition to evoking Morgan's deep, melancholic sensibility. We hear from Morgan himself—his music and his reflections—as well as from his fellow artists, friends and family, in both archival footage and new interviews Heikin shot for the film.

Morgan's life was rich and rough—he also married eight times—and Sound of Redemption negotiates the tricky shoals between his art and the life that informed it.

Making its US premiere, The Life and Mind of Mark DeFriest, from Gabriel London, profiles an inmate who, like Frank Morgan, spent three decades behind bars. And, like Morgan, DeFriest is crafty about devising ways to beat the system. DeFriest's multiple attempts—some successful—to escape exacerbate his already woeful situation—and wear down his mind, if not his will. The film deftly weaves together the byzantine complications of mental illness and crime into the narrative, with a smart deployment of animation to solve the re-enactment quandary. And given this is a journey into the life and mind of Mark DeFriest, and we're never quite sure what to believe, the animation, created by Jonathan Corbiere and Thought Cafe, feels correspondingly off-kilter, like an underground graphic novel that DeFriest himself might have authored. In one of the many twists in the narrative, the psychologist who had initially questioned DeFriest's claims of insanity back in 1981 has a change of heart and conscience 30 years later and affirms that the inmate may indeed have been psychologically damaged prior to his first incarceration. Given the decades-long hell that DeFriest has suffered—for relatively minor felonies—prison has served more to exacerbate than rehabilitate. I came away with a deeper respect for DeFriest; he—and the filmmaker—rarely, if at all, solicit our pity.

To seque from the personal to the national, Last Days in Vietnam documents the frenzied, final chapter of a lamentable period in the American narrative. With access to remarkable footage of both the 45 days leading to the fall of Saigon and the 1973 cease-fire treaty that started the slow retreat, and to the key actors in that drama, Rory Kennedy has crafted a riveting, suspenseful account of history. Her first doc for PBS, Last Days in Vietnam airs on American Experience in 2015, after a theatrical release in September.

Eschewing a re-examination of the Vietnam War, Kennedy focuses on a day-by-day, hour-by-hour account of that chaotic month and on the lesser known characters in this episode-the noble-and-principled-to-a-fault ambassador, who stubbornly delayed the evacuation; the heroic servicemen, who tirelessly evacuated as many American and Vietnamese as possible; the journalists who covered the last days; and the magnanimous citizens who were left behind, but who eventually made it to the US. Last Days in Vietnam is not a revisionist history, but more of tribute to those who tried to salvage something redeeming out of lost cause.

The pain and scars of Vietnam live on among such veterans as Ron "Stray Dog" Hall, the protagonist in Debra Granik's Stray Dog, which won the Jury Award for Best Documentary Feature. Granik had met Hall in his native Missouri, on the set of her 2010 feature Winter's Bone, in which he played a small role. The burly, heavily tattooed Harley rider makes for an engaging presence—running a trailer park, adjusting to married life with his Mexican wife, taking care of his dogs, providing sage counsel and brotherly support to other veterans, joining his fellow bikers on a pilgrimage to the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, DC, and coping with his long-simmering PTSD-related nightmares. Granik wisely eschews narration, cards or sit-down interviews; heeding to the better qualities of vérité documentary, she defers the film to Stray Dog, and we learn his backstory and worldview organically and implicitly. While the film ran a bit long, and could have stood a tighter edit, Stray Dog tells a quiet tale of survival, deep bonding and resolve.

Two additional films that exude the strengths of good observational cinema were Farida Pacha's My Name Is Salt and Eliza Kubarska's Walking Under Water. Pacha's film takes us to Little Rann of Kutch, a vast saline desert in India, where, for eight months out of the year, a nomadic community travels here to harvest salt from the fields. The process is painstaking, precise and laborious, and the tools to do so are antiquated and seemingly inadequate to the task. But the people persevere through adverse conditions and complete their work just before the monsoons come and wash everything away. The remuneration is scant for this Sisyphean endeavor, and the families seem to have few leisurely outlets to countervale the numbing task.

Pacha and her cinematographer, Lutz Konermann, capture a stark beauty in the landscape, taking their time to show us the vastness that seems to engulf the salt people, as well as the odd incongruities—an upside bicycle, a white horse—that underscore its feverish strangeness. And with the people themselves, the filmmakers show an abiding respect and patience, holding steady as the salt people carry out their rhythmic, repetitive processes.

Walking Under Water also follows a nomadic sub-culture: the Badjao spear fishermen off the coast of Borneo. Like the Indian salt people, the Badjao use ancient methods and outdated equipment to carry out their work—and filmmaker Kubarska's cinematographers, Piotr Rosolowski and Lisa Strohmayer, dive down right beside them. The main characters of this story, a seasoned diver and his ten-year-old nephew, make for an endearing generational pair, with the elder teaching both his craft and his wisdom about old traditions and encroaching modernity. In one enchanting scene, the two sit by a campfire, the uncle spinning a yearn about how the Badjao people came from the sea, living among the aquatic creatures. Whether or not this scene was staged or constructed didn't matter to me. Walking Under Water evokes Flaherty's best work, for sure, but also that of the great magic realists of literature. The film earned Honorable Mention for Best Documentary Feature.

Thomas White is editor of Documentary magazine.

From June 23-26, Sunny Side of the Doc, France's international documentary marketplace nestled in the charming historic seaport on the Bay of Biscay called La Rochelle, festively celebrated 25 years since its 1989 Marseille launch.

Over 2,000 professionals from 58 countries in Europe, Asia, South, Latin and North America, Australia and Africa attended, including 244 commissioning editors and buyers, and 468 companies exhibiting. A substantial Chinese delegation with daunting financial resources livened things up considerably and generously hosted evening en plein air receptions and a sunset cruise, which thrilled everyone as we passed by l'Ile de Ré.

After the success of the Asian Side of the Doc last March, there are currently 15 co-productions between France and China about to be signed, whereas five years ago there were none. Brazil, South Africa and Australia also came en masse. This hive of activity spread out over four concentrated days that included panels, pitch sessions, forums, workshops, screenings, working breakfasts and one-on-one meetings. At sunset, the socializing, networking and friendship-building began.

Sessions tackling more thorny issues—government subsidies, contracts, charters, authors' rights, residuals, salaries and fees, pre-sales and co-production treaties—were managed by industry infrastructures like the CNC (France's National Center for Cinema), SCAM (Society of Multimedia Authors), SPI (Independent Producers Union), EDN (European Documentary Network), SATEV (Union of Audiovisual Press Agencies) and the USPA (Audiovisual Producers Union).

The prolific Sunny Lab explored how new media, transmedia, interactive behaviors and mass digital platforms (games, social media, Web docs, online services, shopping, intelligent objects) are impacting audiovisual programming. Six pitch sessions-devoted to history, current affairs, interactive docs, science and nature, politics and society, and arts and culture—gave 35 directors and producers the chance to convince the commissioning editors and buyers of their project's importance, and was a learning curve for all. For those organized and resilient enough to endure 14 minutes on stage under the spotlight, rewards could have an immediate impact on their film's future—if one of these power brokers takes the microphone to declare an interest in the story and a commitment to becoming a partner.

Hard to fathom why there were so few Americans present. I asked several of them about their experiences.

Ann Derry, editorial director for video partnerships at The New York Times says, "I was invited by the festival to speak in the Sunny Lab about transmedia, video and the news business, and what The New York Times is doing in that space. It's my first trip here and I met interesting filmmakers and transmedia producers from different countries. The melding of the documentary film world and the new media community is especially interesting—younger producers are segueing back and forth between different platforms and templates, and more established producers are venturing into new media and transmedia, with fascinating results. My job with the Times is to develop partnerships with producers, filmmakers and digital and conventional broadcasters, so attending Sunny Side opened up the door to more potential collaborations. It was a great experience."

Catherine Allan, senior executive producer at Minnesota-based tpt National Productions, explains, "I am here for the first time trying to line up co-production money from broadcasters for a history documentary. Sunny Side is a great venue and there is a great hunger for documentaries like never before. But co-productions are so complicated, particularly for American producers who don't have a long history of working with international broadcasters, so this is not something you can put in place quickly. It takes a while to develop relationships. I really liked the pitching sessions; the pitches were mostly well organized and their reels were strong. The moderators were very supportive. They did a good job of pushing the decision-makers to say whether or not they would support a given project. I do recommend it."

Donna Roberts, producer/director with her production company, Project Zula, lives in Pittsburgh and Brazil. "Sunny Side was a huge education," she observes. "It's a smaller, more manageable market, where people are more accessible, and distributors, commissioners, sales agents and producers are all speaking the same language. I am in the rough-cut stage of my film from Bahia, Brazil, and I had a consultation with a business affairs expert who identified an important selling point for my project to incorporate into my pitch. As a North American producer/director, I find that we often have a more narrow, limited, homogenous view of the world, while other countries are regularly observing other cultures and different ways of thinking, behaving and communicating."

Filmmaker Vivian Norris, who splits her time between New York and Paris, notes, "Being French-American, co-producing is ideal. Sunny Side is more low key than other markets. There is less distraction, so it's easier to meet decision makers, sales agents and distributers and have time to talk things through, make new contacts, learn about how to sell your film, and find co-production money for upcoming projects. The French have led the way in protecting culture from becoming just another product in a trade deal, and that alone makes the various French players important, but they are also looking to enter into more co-productions and sell more of their films internationally. Sunny Side has become more global than other markets with Asian, Latin Americans and MENA [Middle East North African] regions alongside Europe and North America. My film Obama Mama was in the market and available in the video library for screening, which gave it worldwide exposure. Attending Sunny Side of the Doc helps me understand how to co-produce a film in development by hearing what interests international audiences. It helps me keep up with what is going on with policies in the EU, where many countries offer incentives for co-productions, government subsidies and funds [derived from taxpayer money and TV taxes] towards film production."

Tom Koch, vice president for distribution at PBS International, maintains, "It's the best of times and the worst of times for documentaries—best, because there is a voracious demand; worst, because prices are difficult. Technology getting so cheap means it costs virtually nothing to enter into a project: a small camera, Final Cut Pro, a Mac computer and you're in business. Distribution costs are also low-you can put content up on YouTube for free—and while distribution methods have proliferated (cable, satellite, Internet, etc.), advertising budgets have shrunk.

"There's a huge appetite for docs, but making a living at it is treacherous," Koch continues. "There are only so many slots out there. Finding multiple partners in multiple territories is complicated because broadcasters' tastes, and the audiences they serve, are dramatically different, so you attend those markets where your programs will be most relevant. At Sunny Side I pitched an entirely different set of projects from another market I had attended two weeks before. In my world as distributor, funder and financer, the deal-making process is ongoing, ever-present and constant. It needs time and negotiation before it is completed. I had good meetings with the Chinese, we are doing a big project with the Japanese, and we concluded a very nice deal with French television, so it was extremely valuable for me. I was able to close quite a few deals, actually.

"At Sunny Side you can have substantive conversations with commissioning editors who, in general, can't travel as much to other venues anymore," Koch notes. "Producing has gotten so complicated these days, and they are busy with administrative tasks, but the constraints are not only financial and logistical, they are editorial as well. Today the broadcaster wants something that almost directly connects their immediate audience to the subject. Of course, science and nature programs travel easily, but history programs automatically have to have a local component. In the US there are lots of factual programs but fewer slots for rigorous programs that are journalistically rich or that have a point of view-that is too complicated for most broadcasters."

According to John Lindsay, the former vice president of content at the Seattle-based PBS station, KCTS, "American media organizations—public service, cable, commercial—are drifting away from international marketplaces because of the increasing emphasis on local/domestic stories and reality programs. This disturbing trend reflects the growing disconnect between the US and the rest of the world. Today, you have to think globally, not just locally. How ironic that such tremendous co-production business opportunities are being ignored or overlooked at a time when money for public media in the US is very tight. Asia, and especially China, have huge expanding markets and audiences, and at Sunny Side we met several of their media leaders, who showcased some extraordinary programs from that region. I think American producers and media executives need to attend markets abroad to fully grasp how vibrant global programming partnerships have become. This is a relationship-driven business, and developing those ongoing relationships has never been more important. America's media decision-makers share a responsibility to shape a more informed, alert and engaged public that can face the serious and threatening challenges in the world today."

Madelyn Grace Most is a member of French Film Critics, Union of Cinema Journalists, Foreign Press Association, Anglo-American Press Association, Reporters Sans Frontieres Paris and Frontline Club, London. She writes about film and develops documentaries and fiction films.

New Orleans, Post-Post-Katrina: 'Getting Back to Abnormal' Looks at Life in the Crescent City

By Ron Deutsch

Like some kind of documentary super-group, Andy Kolker, Louis Alvarez, Paul Stekler and Peter Odabashian have come together to make what they have dubbed "the first post-post Katrina" documentary, Getting Back to Abnormal. In various combinations, the first three have had films broadcast in each of the first three decades of PBS' POV series. Alvarez and Kolker's American Tongues was the first film shown when the series launched in 1988; Stekler, Alvarez and Kolker, as a trio, saw their Louisiana Boys: Raised on Politics air in 1992; and Stekler's Last Man Standing: Politics, Texas Style was broadcast in 2004. Getting Back to Abnormal, which premieres July 14, keeps the decade streak alive. The foursome previously collaborated together on Vote for Me: Politics in America, which aired in two parts on PBS in 1996.

Getting Back to Abnormal, as the title implies, takes the perspective that for New Orleans to return to both politics and life as usual after the upheaval of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 is to see it struggle to work out the right blend (we won't say "gumbo") of functionality and dysfunctionality that has made the city so unique, and which has bred so many talented and colorful personalities. The last thing anyone wishes on New Orleans is that it become just another "normal" American city.

The film's main storyline follows the city council re-election of Stacy Head—"the first white person to have been elected from that district in 30 years," explains Odabashian, adding, "which probably, it's fair to say, wouldn't have happened if Katrina hadn't happened." Head gained her seat a year after Katrina, and continues to serve on the council today. The New Orleans Times-Picayune once described her as having an "intense, caffeinated and personal" approach, which is a polite way of describing her infamous outbursts at council meetings.

The other main character of the film is Head's de facto lieutenant, Barbara Lacen-Keller, the director of constituent services. An equally outspoken African-American, she steals every scene she's in with both her wit and convictions.

Filling in the filmmakers' attempt to paint a picture of the Crescent City is the ongoing struggle of what do with the city's poor and the housing projects they lived in—projects that have both plagued the city with death and crime, but that are also believed by many to be vital to the city's culture and history.

Getting Back to Abnormal ends with a quote by the late New Orleanian journalist Lafcadio Hearn, who wrote way back in 1883: "Times are not good here. The city is buried under fraud and maladministrations. But it is better to live here in sackcloth and ashes than to own the whole state of Ohio." It is still today a place some might see as shouldered with unsurmountable problems, but that perception is also what makes New Orleans what it is. And so I began a conversation with the filmmakers by asking, "What is it about New Orleans that made you fall in love with it and want to return with your cameras?"

"I came down to New Orleans [in the 1970s] because some friends of mine had moved there from college in the Northeast," says Kolker. "[There was] something in that alchemy of being 22 and being exposed to a whole world of cultures that were on the one hand exotic, but on the other hand had a sort of craziness and warmth. The experiences I had in my 20s in New Orleans were probably some of the most precious memories I've got in my life. Part of that is because of the time: You grow in a city like that, and it's affected everything that I do, everything in who I am and how I approach life."

"I grew up in the Midwest," says Alvarez, "and New Orleans was about as un-Midwest as you can get. When Andy and I started off making documentaries in the mid-'70s, the only kind of documentaries out there were very earnest. They either had an agenda or they were just a very serious look at a topic. We would have probably made films like that because we were serious about what we did, but in New Orleans nobody wanted to see that kind of stuff. So if you wanted to show documentaries to people in New Orleans, like your friends, and get it on TV so people would actually watch, you had to make it fun. And that was really helpful to us, because we discovered the power of humor when making nonfiction films. And I think we all owe that to New Orleans, because if we had gone to New York, we'd have been making thoughtful, chin-pulling documentaries."

"I went down there, also in my 20s," recalls Stekler. "I was a serious political scientist going down to teach at Tulane, and for me, it was like being on Mars. There is nothing there like what I understood stuff to be like. To a certain extent, all of a sudden, all things became possible. I was interested in politics and all of a sudden I'm writing about politics, I'm running campaigns, I'm helping to run a mayoral campaign, and I bump into Andy and Louis and I go, 'I'm going to make films.' And you were allowed to. This was an amazing place that essentially ruined me as a serious scholar, ruined me in terms of having regular jobs, and it was unbelievably exciting."

Odabashian, a lifelong New Yorker, adds, "In the end, it's just kind of a wonderful place to be, even if you're not eating the food or listening to the music. There aren't that many places in America that are still like that, where you could just enjoy being there."

Because of their personal and professional history with the city, after Katrina hit it seemed they were constantly being asked when they were going to join the packs of filmmakers heading down to New Orleans with video cameras.

"Everybody else was doing that, so we're going to stand back for a bit, we decided," Kolker says. "And we waited, basically four years, while a lot of films were made about the recovery. Some of them were very good, some of them not so good. But almost all of them, we thought, were characterized by an outsiders' viewpoint.

"Part of the thing about New Orleans," Kolker continues, "is that it seems like it's very accessible, but you have to be down there for a while and get into the culture, and then you understand why people behave the way they do, both good and bad. So, four years after, we thought, Now it's a 'post-post-Katrina' era, and maybe this would be a good time to talk about life going on and getting back to the way New Orleans regularly is—which is getting back to 'abnormal.' And we really wanted it to be from the perspective of New Orleanians. So even though we don't live there any more, we felt we could help midwife the New Orleans perspective a little bit."

They decided to get serious about the project when on a trip to New Orleans in 2008 for the funeral of their friend, photographer Michael P. Smith, who had spent his lifetime documenting the city.

"We were basically talking about this as we were on a jazz funeral parade," Stekler explains. "It came from having lived there, having understood that New Orleans is much more complex than many people think of it. It's not just good guys and bad guys. We wanted to make a film that was about the real New Orleans, as opposed to the New Orleans that we saw [in film] that was a lot more simplistic, post-Katrina."

But by that time, "Katrina fatigue," as Alvarez describes the lack of interest by investors in “yet another New Orleans documentary,”, had set in, and so the filmmakers shot for over a year without any outside money.

"We were all staying with friends in spare beds and couches," recalls Stekler, who squeezed time in between his duties as head of the University of Texas at Austin's Radio, Television and Film program. "And at the end of the shoot we'd look at each other and go, 'I don't know if we can afford to do this.' Then we'd think about it, and suddenly we'd all look at each other and go, 'When are we coming down here and doing this again?!'

"I wouldn't recommend this to everybody in terms of making films entirely without any kind of support," Stekler continues, "but this was really a labor of love. It represents the city for three of us that is really part of our lives. And quite frankly, having Peter [the New Yorker] be part of that to keep us honest was really useful as well."

Once they found their main characters in Stacy Head and Barbara Lacen-Keller, the film began to take shape.

"I was resistant at the start to do a film about politics, because I've done too many political films," Stekler admits. "I thought we were going to be doing something cultural. But as soon as it got into Barbara and Stacy, it was clear this was our best story. And it was often not a political story, per se, but much more of a cultural story dealing with race."

"When we started filming in 2009," explains Alvarez, "it was the height of the 'post-racial' talk coming out of Washington, and obviously anyone who's been awake for the last five years knows that 'post-racial' is just deader than a doornail. Maybe in certain aspects of American life we are, but racism has come roaring back to the forefront of civic discourse, and not necessarily in a good way. But there is something about New Orleans that, I don't want to say is positive, but is interesting that it is all up front and out there."

"They don't necessarily use 'weedle words,' the way a lot of the rest of the country uses when talking about race," Alvarez continues. "People in New Orleans will say, 'I'm voting Black this time,' or 'I'm voting White this time.' They'll just come out and say that. Whereas, you would never say that in 'polite company' in the Northeastern United States. What's interesting is that New Orleanians can say that because they have a lot of things on their minds; it isn't just that somebody's black and somebody's white, it's that, 'This person is Black, but they're from uptown, and I'm an African-American from downtown, so I'm not supporting them because they're from uptown.' It's not about racial solidarity, it's really about tribal solidarity. And that works across all racial groups there. In New Orleans, everybody knows that's how the game is played and that's how people think of themselves. So there's not a delusion; a lot of America has this delusion that there's somehow this even-handed, not color-conscious, society, and it's just simply not true. And in New Orleans they know it's not true and they're not pretending that it is. And so we wanted to try to capture that in the movie. We wanted to show people being pretty frank about their racial identity and racial ideas, no matter whether they're black or white."

"People in New Orleans look at Stacy Head, or someone like Stacy Head, and they're starting to look past the supposed racial insensitivities," adds Kolker. "They're saying, 'Oh yeah? Well, you know what? I don't care [what color she is] because this lady is getting something done, and she's smart, and she knows how to work the system, even if she's standing up there and screaming at people. She is going to get something done.'"

"Then we met Barbara," explains Stekler, "who's her chief aide dealing with the community, and it was like, 'Where did this person come from?' So the combination of the two of them is amazing. White and black; tall and lean versus short and stocky; measured lawyer versus somebody incredibly emotional. Barbara also has the street chops-she was nicknamed the 'Mayor of Central City' by [former New Orleans Mayor] Marc Morial. She came out of the Desire housing projects in the Lower Ninth Ward. She was married to a very famous musician, which is not part of the film. So Barbara had the street cred and was also not shy on camera. That led to things like on Election Day, when she's quasi-narrating what's going on before she has the confrontation with the guys [supporting Head's opponent] distributing the 'No Racism/No Head' posters in the truck."

But the big question that hangs over the film is whether New Orleans can, indeed, find its way back to "abnormal."

"After Katrina, there was concern," Alvarez responds, "and I think we share that concern, that somehow something had been irretrievably lost. But here it is, nine years later, and I think New Orleans continues to abide."

"There's no doubt that when you have a cataclysmic event like Katrina, the city is going to change," adds Kolker. "Clearly the demographics changed. They didn't change as much as I think people thought they might, but they certainly have changed. Certain things that were relatively inaccessible now have become very accessible—like when Mardi Gras Indian parades have their routes published in the newspaper; beforehand you couldn't find them unless you knew where to go. That seems like a small thing, but the point is that when the culture comes out into the open, inevitably it's going to change. It's going to become somewhat more universal, it's going to become somewhat more commercial. But New Orleans has always been a commercial city, in that sense. It's always sold its culture to tourists. It's becoming even more so, and when that happens you do eventually get a kind of an imitation, almost an imitation of an imitation, that meta-business starts to happen, and certainly it is happening in the city. That inevitably does change things, but at its core, the city is still going on. Much of it does remain the same. How long it will remain the same? That's anybody's guess."

"It changed our lives when we lived there," Stekler says, "and it continually creates new New Orleanians over time. Part of the joy of making this film was, at least for me, to have one last look at that."

"One of the reasons we had the quote by Hearn at the end of the film is to make the point that 150 years ago people were complaining about the place," explains Odabashian, "and yet the city keeps attracting people like us, who came 40 years ago and fell in love with the place and became, for better or worse, some of the curators of New Orleans culture, along with a lot of other people. And now, there are young people coming down there and doing the same thing."

"One of the things when you're not from New Orleans," Odabashian concludes, "is when you show up and fall in love with it, you're condemned to be told by people who are from there, 'Yeah, it's okay now. But you really missed the great days. The great days were 10 years ago.'... or '20 years ago.' And you can always say that, but the great days continue. The place changes. It's not immovable, but there's something fundamental that never seems to change, and that's what all of us who love New Orleans are happy about."

Getting Back to Abnormal airs July 14 on PBS' POV.

Ron Deutsch is a contributing editor to Documentary Magazine. He has written for many publications including National Geographic, Wired, San Francisco Weekly and The Austin American-Statesman. He is currently associate producing the documentary Record Man, about the post-war music industry.

It is not surprising that the Tow Center for Digital Journalism's research project, Video Now—which examines current trends of news publications' video departments, focusing on October 2013 through February 2014—comes with this disclaimer: "The organizations that we visited and feature may all have moved on to new models by the time you watch this." It is a swiftly shifting world, with new leaders emerging and partnerships being formed everyday in the race to produce quality video content and maintain and grow audiences. Publications formerly steeped historically in print are forging ahead into unchartered territories to create video content not only that complements and adds dimension to written pieces, but also showcases short-form and interactive documentaries that stand on their own as forms of journalistic storytelling.

Video and multi-media content produced by newspapers and magazines now plays a substantial role in targeting new audiences, along the way creating opportunities previously unavailable to documentary filmmakers. For the readers of long-existing print publications, this content often comes as a surprise. "I still get that all the time: ‘You're a video producer at The New Yorker? What does that even mean? I didn't know they do video,'" says Sky Dylan-Robbins, video producer at The New Yorker. Currently, The New Yorker primarily produces all of its content in-house. The video department, consisting of two people, produces two types of nonfiction videos: up to three videos a week that live independently on newyorker.com and, in conjunction with writers and editors, as many as six videos a week that further augment written content.

Asked of the rewards of working full-time as a filmmaker (Dylan-Robbins shoots and edits many of the pieces herself) at a publication famously known for print, she responds, "As filmmakers, we are at this turning point in how people consume media. It's so great that we can make films and video content, and that that is what people are looking for. It's cool we can be part of the media revolution, so to speak."

This revolution also means a redefining of terms. It took a while during our Skype chat for me to realize that when Dylan-Robbins discussed supplementing of video or multimedia content for written articles for the "magazine," she was referring to The New Yorker as viewed on a tablet device. Tablets have shifted the entire publication paradigm, allowing the differentiation between free or paywall-protected content online and a model more in line with a traditional print subscription model. How a publication's content is viewed, shared and ultimately paid for by its audience factors into viewership, video budget and revenue.

Founded in 1925, The New Yorker's voice was developed, refined and ingrained in the expectations of its readership long before video came along. There is an expectation of consistency of voice throughout all its storytelling, which can prove challenging for a relatively young department, says Dylan-Robbins. "Everyone is thinking about how they can maximize their online presence while staying true to their brand," she explains. "The New Yorker is such an institution, so everyone has been thinking very carefully about how we can shift things to this new world while staying totally true to what The New Yorker is and always has been. There is always this trial-and-error period. We do something and say, 'Wow, that worked so well. Let's iterate.' Or, 'That's not the best, but now we know we can improve.' It's three steps forward with maybe a half a step back. Then more steps forward."

Kasia Cieplak-Mayr von Baldegg, executive producer of video at The Atlantic, found similar challenges when she was building her department. Originally hired to curate and license a mix of videos from around the Web, with a focus on nonfiction, Cieplak-Mayr von Baldegg explains what the process was like from the very beginning: "We set out to answer two questions: Was there an audience for Web video on theatlantic.com? And would our advertisers be interested in video? The answer to both questions turned out to be yes, and two years later we launched an in-house production department dedicated to creating original video for the site."

Cieplak-Mayr von Baldegg's team currently consists of herself and three full-time video production staffers. Their department is growing rapidly with the recent hire of a curator to continue licensing videos and working on partnerships and audience development. She plans to add two more full-time producers this spring. "We get to explore what Atlantic journalism, with more than 150 years of history behind it, looks like in video," she says. "It's a thrilling opportunity to develop new formats of nonfiction storytelling built for the Web, but it also comes with challenges: How do you produce quality journalism and adhere to high production values while moving fast with an incredibly lean team? How do you innovate constantly to keep up with the rapidly evolving world of online video? There's no proven formula—but I love that. It gives us a chance to build something from the ground up."

Asked what advice she has for filmmakers looking to work with The Atlantic, Cieplak-Mayr von Baldegg says, "Well, it's not that mysterious. We look for compelling topics that shed light on some larger theme or idea, and strive for clean, beautiful production values. There's a kind of directness in Web video that we appreciate too. And we experiment constantly!" Cieplak-Mayr von Baldegg says she's proud of the broad range of formats her video department explores. Some examples of her favorite pieces for The Atlantic: "Where Time Comes From, a documentary about a scientist at the US Naval Observatory, explores a very big question in a lovely, visually intriguing way. SODA POP COKE, an experimental infographic of sorts, captures the charms of the famous Harvard dialect study in an inventive way—and it's our biggest viral hit to date. Dr. Hamblin's video series on health topics, If Our Bodies Could Talk, is both funny and informative."

The New Yorker's Dylan-Robbins offers this advice for filmmakers: "We love getting submissions, but we don't take pitches. We look at almost fully formed videos or rough cuts; it is easier to see if it is our voice. We pay for the ability to show it first, then the filmmakers can do what they want with it 90 days later." Among The New Yorker videos of which she's particularly proud, Dylan-Robbins cites Peter Rosenberg: A D.J. Who Actually Plays Records, which adds texture to a written piece; Thank You for Vaping, a 15-minute documentary that demonstrates that an of-the-moment topic can be explored in a different way; and Inside the Home of the New Year's Ball, an evergreen piece on a unique part of New York history.

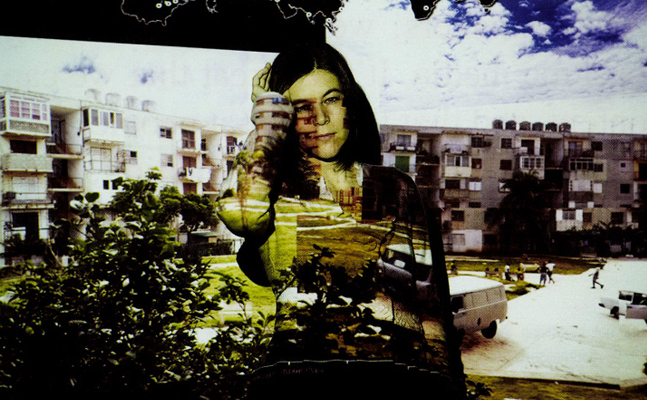

For a filmmaker, working closely with a publication to create an original work can provide its own unique opportunities. HIGHRISE director Katerina Cizek worked with The New York Times Op-Docs to create the interactive documentary A Short History of the Highrise and saw the collaboration as an incredibly interesting and educational process. She cites the in-depth editorial conversations and The New York Times' rigorous fact-checking as invaluable components of the creative process. "We think of the Times as 'deep collaborators,'" she maintains. "The project was an example of the sum being greater than the parts. Neither of us could have done this alone" Cizek and HIGHRISE producer Gerry Flahive were able to bring their experience and knowledge of "vertical living" to the collaboration, and The New York Times opened their archives, and digitized and provided clearance for the images.

The project, which originally began as a single film, grew into three interactive films because of the hands-on collaborative process. Op-Docs is now widely known as an opportunity for documentary filmmakers to expose their work to new audiences, but a project like The Short History of the Highrise showcases what a publication can offer a filmmaker outside audience-building, including the process of working with a highly trained news editor and the opportunity for prestigious awards. The Short History of the Highrise was honored with both a Peabody Award and a First Prize for Interactive Documentary at the World Press Photo Multimedia Awards this year.

On these types of collaborations Cizek advises, "Publications are like all relationships. Best not to try and ‘sell' them something. Rather, find a partnership that works on both sides. Presenting a ‘jeweled box' rarely works." Flahive adds, "These partnerships are more promotional than a business model; no one is writing huge checks to each other, but our audience grew and 5,000 tweets were shared around the world the first week A Short History of the Highrise launched." On working with The New York Times Op-Docs he says, "We are not journalists; we are filmmakers. Opinion is prized. The POV of the filmmakers is part of the brief." He also advises filmmakers to embrace the opportunities that creating online work offers. "Most filmmakers think linearly, so there is a conceptual barrier," Flahive notes. "Most video online could be seen on TV. Web should be the plasticine, the playground. Filmmakers need a more open attitude to what a documentary can be."

In the end, quality content is what publications are looking for, and this is just the edge a documentary filmmaker has in this brave new world. "The advantage for filmmakers is their time with their subject and their strong point of view," Cizek asserts. "This is something they can bring to publications, as most of a newsroom's day-to-day is focused on daily news."

Whether working with a publication to create original content or to gain and build an audience for a longer personal project, documentary filmmakers are finding that collaboration has its advantages, but it is also important to know when going into a partnership with a publication that its editorial and production staff will have their own set of priorities such as tone and voice, and strict fact-checking standards if partnering with the news department. This may challenge a filmmaker's flexibility, but Cizek's final advice on our Skype call is the best takeaway for documentary filmmakers: "Fight the good fight, but don't take it personally."

Amanda Lin Costa is currently directing and producing the documentary The Art of Memories and adapting the true life story of Annie Londonderry, the first woman to go around the world on a bicycle, into a feature film.

If you were looking to see independent films about Quidditch competitions, the life of Olympic diver Greg Louganis, the wild boar invasion in the Netherlands, or the man inside of Big Bird, AFI DOCS (formerly Silverdocs) was the place to be in June. The international festival, celebrating its 12th year in the Washington, DC area, offered 84 feature and short documentaries and 14 premieres over five days.

But it wasn't just cultural topics that attracted viewers. Social issues docs were big. There were stories about homeless high school students trying to graduate (Anne de Mare and Kirsten Kelly's The Homestretch), the crackdown on whistleblowers since 9/11 (James Spione's Silenced), the rise of young activists and social media during Arab Spring (Greg Barker's We Are The Giant), and even more that were critical of government of all sizes.

With the loss in 2013 of Discovery Communications as a main sponsor, the new name, the discontinuing of the festival's popular industry conference, and the departure this year of longtime director Sky Sitney, there were some concerns among filmmakers that the festival would continue to scale back this year. The gradual shift in screening sites from the Silver Theatre in Silver Spring, Maryland to an assortment of venues in downtown Washington, DC was of particular concern.

"I totally appreciate that it all used to be centered in Silver Spring, and people miss the old days," says interim festival director and filmmaker Christine O'Malley (Wordplay). "But now we have the best of both worlds, with DC and Silver Spring. Change here is growth change." She adds that AFI feels the festival is a priority, and is "committed to making it work." This year AT&T came on as the presenting sponsor, and Penn Social on E Street in DC was added as a meeting hub.

"They nailed it," said first-time director Nicole Boxer (How I Got Over). Boxer's film, about a group of DC homeless women who write and perform a play about their lives, had its world premiere in front of a sold-out crowd. "If you're a social impact filmmaker, there is no reason not to be at AFI DOCS." For Boxer the proximity of policymakers is unique to the festival, and there were plenty present this year, including her mother, Senator Barbara Boxer.

As a producer, Nicole Boxer (The Invisible War) has brought other films to the festival. The difference for her this year? There just seemed to be more films "that inspire, change and have impact." This was also the second year of the Policy Engagement Program, a Capitol Hill tutorial for filmmakers on how to engage leaders in an issue and influence public policy.

Boxer's characters were also on hand, as were others: Big Bird's creator, Caroll Spinney, from Dave LaMattina and Chad Walker's I Am Big Bird; actor Hal Holbrook, from Scott Teems' Holbrook/Twain: An American Odyssey; and magician James "The Amazing" Randi, from Justin Weinstein and Tyler Measom's An Honest Liar, which earned the Audience Award for Best feature. There was even a Quidditch lesson—the game invented by author JK Rowling for her Harry Potter series—for all interested players after the screening of Farzad Sangari's Mudbloods, a doc about college teams competing for a Quidditch World Cup. "It is a grand slam, anytime you have participants at premieres," O'Malley maintains. "These are the moments that move me." Several volunteers from the Freedom Summer campaign of 1964—a time explored in Stanley Nelson's new film Freedom Summer—were on hand. "It was remarkable," comments O'Malley. "This is why we all do what we do."

Social impact and outreach were also the subjects of several panels. One panel sponsored by IDA--Getting Real: Creating Change from the Inside Out--centered around last year's AFI Docs selection, Documented. (Documented aired on CNN, and will air again July 5.) The film's subject and director, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Jose Antonio Vargas, joined Frank Sharry of America's Voice, Ryan Eller of Define American and Emily Verellen of the Fledgling Fund to explain to filmmakers how to plan, execute and evaluate a social media campaign. Documented talks about the issue of immigration on a heart level. For Vargas, it started with his story as an undocumented immigrant from the Philippines. He then used his story to "open people's minds" and reach others—who in turn become allies. "Every civil rights issue needs them," he said. The panel agreed that cultural shifts come before political ones.

The second panel, also presented by IDA, focused on a film from this year's AFI DOCS, Rachel Lears and Robin Blotnick's The Hand That Feeds, which tells the story of food workers who unionize, as a test case for outreach. Former SILVERDOCS Festival Director Patricia Finnernan walked the filmmakers through the different levels of outreach that can be achieved.

A later panel, "Public Media Content that Matters, Engagement that Counts," sponsored by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), offered a further course in outreach. According to Eliza Licht of POV, the first thing you need "is a great story." The panel focused on Joe Brewster and Michèle Stephenson's American Promise, Katie Dellamaggiore's Brooklyn Castle, and Rory Kennedy's Last Days of Vietnam.

Academy Award-winner Alex Gibney was the focus of the Guggenheim Symposium for his work in films such as Taxi to the Dark Side, We Steal Secrets: The Story of WikiLeaks and Mea Maxima Culpa: Silence in the House of God. The Symposium honors what AFI calls "masters of the non-fiction art form." Previous honorees have included Barbara Kopple, Spike Lee, Albert Maysles, Frederick Wiseman and Errol Morris.

"Gibney's personal drive to find and expose truth in film makes him one of the most important documentarians of this and any generation," says O'Malley. Ann Hornaday of The Washington Post moderated the discussion with Gibney. "I think Ann is a wonderful interviewer and conversationalist, so it was interesting to hear more about Alex's life and the people and experiences that have had a major impact on him," O'Malley continues. "I really enjoy the way that symposium is set up because it lets you get acquainted with the filmmaker in a way that feels very personal-kind of like Inside the Actor's Studio for docs."

Opening night featured the world premiere of Holbrook/Twain: An American Odyssey, about actor Hal Holbrook's decades-long role of playing the author Mark Twain on stage. According to freelance writer Natalia Megas, "The night was spectacular. The film was surprisingly good, and I say surprisingly because the title threw me off a bit. It was also nice to have the director [Scott Teems] and Hal Holbrook there. They were very approachable."

Independent producer Maryanne Culpepper agreed. "It's talking one-on-one with key creatives that's really interesting, and AFI DOCS offers this. It's an excellent exchange of thoughts and ideas. It's a mutual learning environment."

For first-time AFI DOCS participant Will Sweeney (Back On Board), the festival was "great for us. We had a great response, incredible crowds and a standing ovation." The biographical and archival film premiered here, and Olympic gold medalist Greg Louganis was on hand to answer questions. Sweeney, primarily a narrative feature producer (The Royal Tenenbaums), just dipped his toes in the doc pool with Back On Board. As a first-time doc producer, he found the creative process amazing and awesome, and would do it again. In the end Louganis' story about being accepted as gay is "about all of us, the progress we have all made".

Erica Ginsburg, executive director of the Silver Spring-based nonprofit Docs In Progress, has attended all the incarnations of the festival, dating back to 2003. The presence of about 100 filmmakers and characters, like Oscar the Grouch, "harkened back to the old days," she says. "It was a great opportunity. I hope we don't lose that kind of interaction." Ginsburg adds that last year was challenging with all the changes to the festival, but she felt the staff did listen to feedback; for example, they re-established a meeting space for filmmakers to meet and mingle, at Penn Social in downtown DC.

"This year they also did a better job of insuring that the Silver Spring location was not forgotten," Ginsburg points out. "They have almost created two festivals." She notes that in the past you could have that serendipitous moment when you heard about a film or a panel, and just went to it. "Now, you have to be more organized. Yes, there is huge hole in the industry without the professional conference, but the quality of the films is still high."

Culpepper adds that AFI DOCS "has turned into more and more of a film festival, attracting not only those in the industry but the general public. I think it has an important role to play in getting great nonfiction storytelling in front of audiences. Festivals like AFI DOCS offer a mainstream entertainment venue for great factual stories. They offer the general public a chance to view together as a community—to discuss, to critique, to hear from the directors, producers and writers. It's a wonderful creative outlet-and a great way for audiences to see something in a theater that isn't a remake or sequel of the last box office smash."

Other audience favorites included Michael Rossato-Bennett's Alive Inside: A Story of Music and Memory, about an innovative music-based program that has proved effective in addressing the effects of dementia and Alzheimer's disease. According to author Liliane Mavridara, "Watching the transformational results music has on bringing back memories to people with memory-loss diseases was beyond just moving. There was a gentleman who suffered from MS and who had lost any interest or hope in life. Through listening to his favorite music from before, he was enlivened in front of our own eyes. The film was highly inspirational."

The shorts programs came back with force this year, too. Among the big hits: Ned McNeilage's Showfolk, about the residents of the Motion Picture & Television Retirement Community in Los Angeles; Marcelo Kiwi Bieger's The Chilean Elvis; Willem Baptist's Wild Boar, about a small village in the Netherlands overrun by a large pack of wild boars; and Sam Thonis' Beyond Recognition: The Incredible Story of a Face Transplant, which won the Audience Award for Best Short. winner.

Life Itself, Academy Award nominee Steve James' biographical film about the late film critic Roger Ebert, closed the festival. Ebert was a big fan of films that opened people's hearts. Many of the docs this year at AFI DOCS achieved that goal.

Lauren Cardillo is an award-winning Washington, DC-based filmmaker who was co-producer of the 2007 Silverdocs selection STAND UP: Muslim American Comics Come of Age.

Profile: The Documentary Media Studies Graduate Certificate Program at The New School

The Media Studies program at The New School is one of the oldest in the United States. Marshall McLuhan's colleague John Culkin brought his Center for Understanding Media to The New School in 1975, and The New School began offering the master of arts degree in media studies, one of the first graduate programs of its kind. Today, the program encompasses media theory, media business and media technology; students create their own media projects, ranging from documentary and dramatic films to websites and other online media, installations and multi-media projects. These programs prepare students to advance in almost any career direction in the rapidly evolving global media industries.

Now in its eighth year—the Documentary Media Studies Graduate Certificate launched in 2006—the program was deliberately constructed as a graduate certificate in order to respond to students looking for a coherent, sequenced, specialized program in the field of documentary.

Deanna Kamiel, the current director of the program, is a documentary filmmaker and Guggenheim Fellowship recipient with a longstanding career in public broadcasting at the CBC and PBS. Documentary spoke with Kamiel about the mission of the program and how it ties in with the New York City community.

Can you give a background on the program, and how you feel it relates to other film studies options in the US?

Deanna Kamiel: At the heart of the Documentary Media Studies Graduate Certificate program at The New School is an emphasis on theory and practice, combining courses in documentary history and theory with production technique and technology. The emphasis on praxis—and the making of socially engaged media work—is the central mission of our department; the School of Media Studies is the first media studies department in the US dedicated to applied critical thought.

What distinguishes this program is our configuration as a one-year, full-time intensive curriculum, culminating in an end-of-year public screening festival, Truth Be Told, featuring the original films made by each of our students throughou

t the academic year. Also distinctive is our approach to media-making. We emphasize a sense of cinema, draw from film and screen language, and offer students the opportunity to explore the full range of documentary form, including hybrid, experiential and visionary modes of nonfiction work.

Each year's class of 15 to 17 students is a cohort, taking mostly required courses [the year includes five required courses and one elective] together throughout the two semesters, collaborating and crewing for each other on class assignments and each others' individual films. After graduating from the certificate, students can, if they choose, apply their 18 credits from Documentary Media Studies to the master's program in Media Studies.

What are resources in the city and the region for students and faculty?

Central to our program is our location, New York City, a world capital for documentary and an inexhaustible world of stories and discoveries for filmmakers and media artists. We are privileged with access to significant documentarians, filmmakers and production companies, whom we invite to our Doc Talks series of guest workshops and master classes. Recent guests and visiting artists have included Laura Poitras, Jem Cohen, Albert Maysles, Su Friedrich, Peter Hutton, Tammy Cheung, Tanaz Eshaghian, Nina Davenport, Alan Berliner, Jason Spingarn-Koff from Op-Docs at The New York Times, editor Jonathan Oppenheim and sound designer Ernst Karel from Harvard's Sensory Ethnography Lab.

New York is also a magnet for internship and entry-level job opportunities in the field.

Our production facilities include an Avid editing lab and a well-equipped film office that offers an HD camera package (Panasonic 150 or DSLR cameras, tripod, LED portable light kit, audio kit), as well as shoulder mounts, steadicam rigs and portable dollies. Camera packages are offered to students in three-person crews for the duration of the first semester, and are readily available throughout the rest of the academic year.

Where are the students from? What are their career backgrounds?

The Doc Studies Certificate program attracts talented students from all over the world and across the US. In fact, we have one of the highest international student populations in the university: from Columbia, Chile, Denmark, Latvia, India, Pakistan, Mexico, Australia, New Zealand, the Netherlands, Norway, France, Canada, Lithuania and Estonia. The dynamic mix of international and American students makes for new ways of seeing.

Our students have a variety of career backgrounds: journalism, the social sciences, anthropology, international affairs, photojournalism, critical theory, graphic design, urban studies, history, political science, NGO-field work in crisis zones and rights-watch organizations.Their commonality resides in their fascination with the real, the actual emerging world of events and ideas—what Al Maysles calls "the documentarian's providence."

Like The New School itself, we have a significant reputation outside the US as well. We also have a vital and close-knit alumni community, which represents us worldwide and attracts new students by word-of-mouth. We stay in touch by social media; we have a community blog and Facebook page.

What are the job prospects for your graduates?

Our graduates have been very successful in the job market both here and internationally. Many are working in broadcasting—HBO, PBS, MSNBC, MTV, CBC, the Discovery Channel, DR1 [Danish Public Television]—and for online production organizations. Several have formed their own production companies and a great many are working as editors, assistant editors, cinematographers and producers.

- In Copenhagen, Anders Birch just aired the sequel to his film Denmark on the Prairie for DR1 to great reviews and high ratings. The original film, which aired last year, made celebrities of the citizens of Elk Horn, Iowa, a prairie town that maintains its Danish cultural heritage.

- At New York Magazine, Sarah Frank was senior director and editor for the magazine's Web doc series before recently joining the video startup NowThis News as senior producer.

- Sue Hagedorn's production company Seedworks has made a number of documentaries on social issues. In 2013 her film Deputized, on the social politics surrounding the murder of Ecuadorean immigrant Marcelo Lucero, was broadcast on PBS and won the Humanitarian Award at the Long Island International Film Expo.

- Laura van Schendel was a video editor for NBC before returning to the Netherlands to produce television documentaries.

- Maya Mumma, who began as an intern on the award-winning feature Restrepo, co-edited the recent Which Way Is the Front Line from Here? The Life and Time of Tim Hetherington. She also edited several other doc features, including HBO's Whoopi Goldberg Presents Moms Mabley.

- Julia Reagan works at @radical media, where she was associate producer for Joe Berlinger's current film, Whitey: United States of America v. James J. Bulger, a CNN/@radical media co-production, which had its world premiere in January at the Sundance Film Festival.

A great many graduates have also had significant success on the festival circuit. Trina Rodriguez produced the award-winning High Tech Low Life, about Chinese Internet dissident bloggers, which was on Indiewire's list of Best Documentaries of 2013. The films of both Donya Ravasani (American Imam) and Eric Rockey (Vulture Culture) were featured at DOC NYC. In 2013, Ivana Todorovic's When I Was a Boy, I Was a Girl premiered at the Berlinale, and won the Best Documentary award at Dokufest in Prizren, Kosova. Ivana currently works for a production company in Sarajevo, where she is making a documentary for Al Jazeera's Balkan series. And Jeremy Cohan received the Directors Guild of America's Jury Award for his student film After.

What are options for students to work with a variety of digital media? Can you describe some recent projects?

Digital interactive media first came to our program as a means for students to create outreach, promotion and distribution for their thesis films. The prime mover in this area is one of our faculty, Amir Husak, a documentarian and digital media artist, who has created an elective course for documentary and expanded media. Several of our students have also been involved in gallery installation and online Web work, combining political, critical and aesthetic thought across a range of documentary subjects.

What are the future plans for the program? As the media world is changing so rapidly, how would you like the program to grow, or change, or both?

Our future plans for the program include more concentration on emerging media and expanding documentary form. At the same time we look forward to intensifying our core courses in cinematography, sound design and documentary practice. We are proud of our emphasis on open-form documentary and would like to extend our cinema-centered approach to a second-year MA that would focus at greater length on socially engaged work, the politics of place and geography, and expanded digital media aesthetics.

Wanda Bershen is a consultant on fundraising, festivals and distribution. Documentary clients have included Sonia, Power Trip, Afghan Women, Trembling Before G*D and Blacks & Jews. She has organized programs with the Human Rights Film Festival, Brooklyn Museum and Film Society of Lincoln Center, and currently teaches arts management at CUNY Baruch. Visit www.reddiaper.com.

The Documentary Media Studies Graduate Certificate Program at The New School

Duration of the Program

One Year

Degree Offered

Graduate Certificate, with 18 credits applicable to a master's in media studies at The New School

Components of Program

Documentary history and theory; production technique; technology

Number of Students

15 to 17

Internship Placement Opportunities

No formal internship program, but with The New School program's access to the New York documentary community, students arrange internships and entry-level positions upon graduating.

I learned about film critic Roger Ebert's death via a text message from a fellow film school graduate. I'm not prone to mourning famous figures I've never met, so the sting of his loss was unexpected, immediate and powerful. It was his collection of film reviews, The Great Movies—a gift to me from my mother in 2003-that first made me recognize how film writing could be both accessible and profoundly moving. More importantly, this collection keyed me into a focused and inspired way of watching films. From its special place on my bookshelf, my now well-worn copy was my first real guide to the best that cinema had to offer.

For diehard cinephiles like myself, no discussion of film criticism is complete without mentioning Ebert. Admire him or abhor him, he left his indelible imprimatur on the collective conversation about movies. This native Chicagoan took film criticism—a field dominated by the New York intellectual set—and democratized it for anyone fostering a love of movies.

For 46 years, Ebert was, as the Chicago Sun-Times dubbed him, the "Movie Answer Man"; his column was also syndicated in over 200 publications in the United States and abroad. His great influence didn't stop with periodicals: He published over 20 books, collaborated on several screenplays and appeared with fellow Chicago-based critic Gene Siskel on several widely syndicated movie review shows.