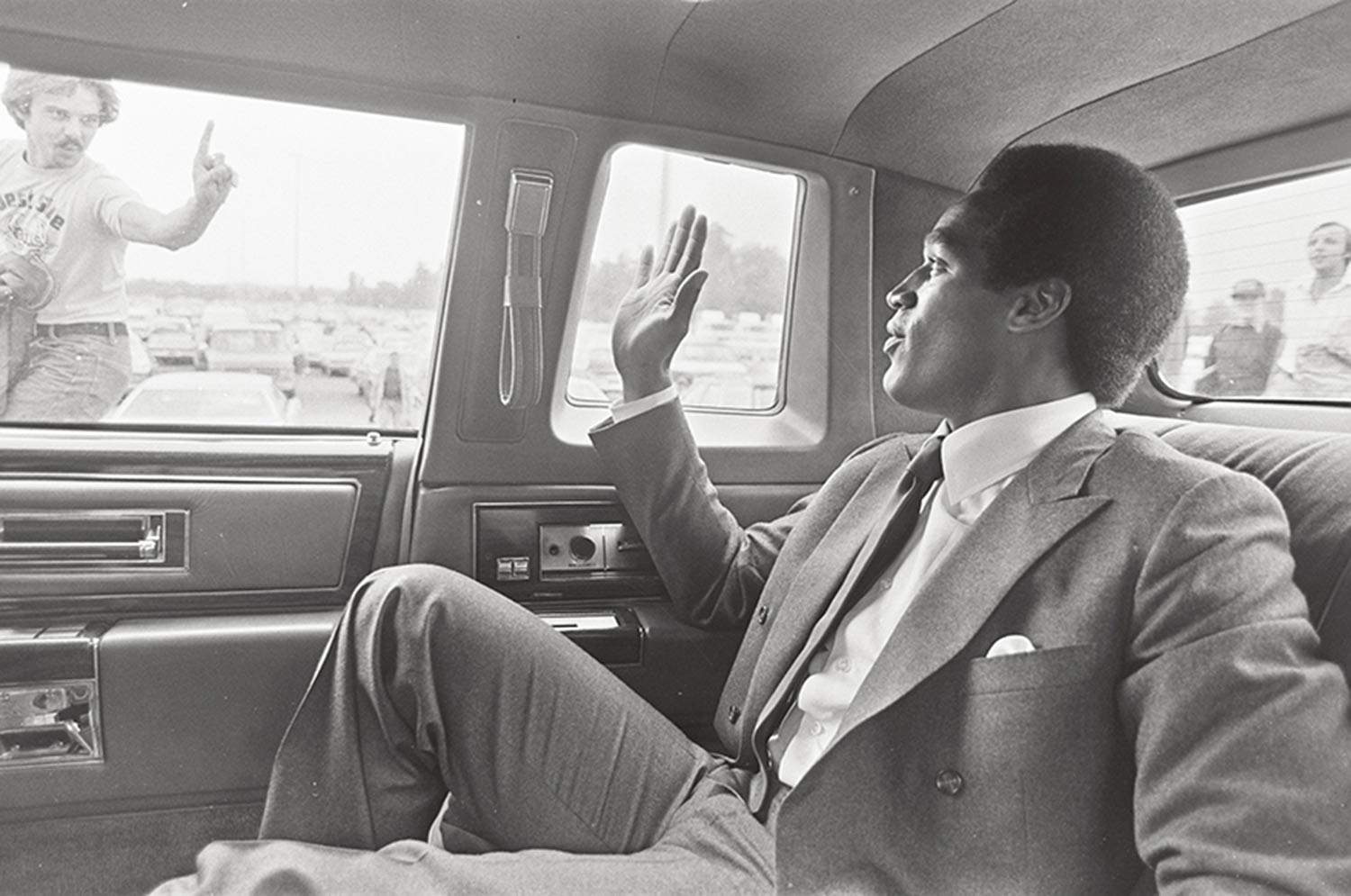

Criminal prosecutions and civil litigation can make compelling subjects for documentarians. Indeed, documentary films that have used legal cases as a vehicle to explore broader social and cultural themes, or to expose individual or systemic injustice, are legion. Ben Cotner and Ryan White’s 2014 film The Case Against 8, which told the story of the legal fight to overturn California’s Proposition 8 ban on same-sex marriage; Stephen Maing’s 2018 film Crime + Punishment, which focused on a group of whistleblowing New York Police Department officers—the “NYPD 12”—who alleged in a lawsuit that they had been pressured to engage in illegal quota practices in their police work, and retaliated against when they refused to do so; and Ezra Edelman’s 2016 film OJ: Made in America, which chronicled one of perhaps the best-known criminal cases of all time, the trial of O.J. Simpson: These are just a few examples of the many documentary films that have focused on legal cases.

Through their pro bono, pre-publication advising work for documentary filmmakers and other investigative journalists, attorneys at the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press often encounter projects that delve into the details of a specific criminal prosecution or civil lawsuit. And, through that work, these attorneys have identified some of the pros (and potential legal pitfalls) of documenting legal cases in the United States.

One of the benefits of pursuing a project that chronicles a civil lawsuit or a criminal case is, generally speaking, ready access to relevant documents and information found in court records. Court filings often contain a treasure trove of documentary evidence that filmmakers can use. In the civil litigation context, for example, parties frequently file what are called motions for summary judgment that lay out their case. Such motions are generally accompanied by hundreds—in some cases, thousands—of pages of exhibits. Those exhibits can include key documents, as well as transcripts of deposition testimony from experts and other important witnesses. Federal courts and many state courts make motions for summary judgment and other court filings available in searchable, online databases, making them much easier (and faster) to obtain than, say, public records requested under the federal Freedom of Information Act. And because in the United States there are strong legal presumptions of public access that apply to court proceedings and documents filed in connection with them, sealed court filings and closed courtrooms should be rare.

From a legal perspective, relying on court records can also have an added benefit for filmmakers—at least in some jurisdictions. Some courts recognize a fair report privilege that can protect documentarians and other journalists from defamation liability for including information in their work from an official public document—like a court decision, a filing in a court case, or a transcript of a court proceeding—even if the information is false and defamatory. Unfortunately, not all states recognize the fair report privilege and, even where the privilege is recognized, the protection it affords can vary. That said, relying on an official document, like a court filing, as a source of information is generally a good practice, and it can help shield documentary filmmakers and other journalists from potential legal liability.

Though court filings are, generally, publicly available, obtaining access to other relevant documents and information concerning a legal case can sometimes be a challenge. Documents that are merely exchanged between parties during the discovery phase of a civil lawsuit, for example, are not subject to the same presumptions of public access that apply to documents that are filed with a court. And, in some cases, courts will enter protective orders that prohibit parties and their attorneys from sharing documents and information they obtained through discovery with third parties, including documentary filmmakers. A protective order can thus limit a documentarian’s ability to obtain access to relevant documents and information in a particular case. In addition, attorneys representing parties in civil and criminal cases have certain professional duties, including a duty of confidentiality to their clients; as a result, they may be unable—or unwilling—to speak to a documentary filmmaker in any detail about their client’s case, or they may limit a filmmaker’s access to out-of-court discussions about that case.

Another significant potential hurdle that documentarians may face when chronicling a legal case is the inability to film (or obtain footage of) key events that occur inside of courtrooms. Audio and video recording—and even live broadcasting—is permitted in civil and criminal cases in some state trial courts in the United States. The O.J. Simpson murder trial, for example, was famously televised. But rules governing the use of video cameras in courtrooms vary from state to state and even from courthouse to courthouse. In some jurisdictions, whether any audio or video recording is permitted in a courtroom is up to the individual judge. Accordingly, documentarians who want to film a trial, hearing, or other in-court proceeding in a state court case should check to see what rules apply in that court, and plan ahead to obtain permission to film.

Documentarians should not count on being able to film (or obtain audio from) any federal trial court proceedings, however. Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 53 prohibits photography and broadcasting of judicial proceedings in federal criminal cases, including trials. In addition, only three federal district courts—the US District Court for the Northern District of California, the US. District Court of Guam, and the US District Court for the Western District of Washington—permit any recording of proceedings in civil cases. Those district courts are part of a limited pilot program that allows for the recording of some proceedings in select civil cases with the consent of all parties. Given the limited nature of that pilot program, however, it is unlikely to be of any practical use to a documentarian working on a film. Some federal appellate courts, including the Supreme Court, make audio recordings of oral arguments available to the public, and the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit makes video recordings of oral arguments available; however, none of those courts permit documentarians or other journalists to film proceedings inside courtrooms.

One of the most concerning potential pitfalls of documenting legal cases is the heightened risk of receiving a subpoena. When documentarians are interviewing or filming participants in an ongoing civil or criminal matter, they should be aware of the possibility that other parties to that legal case may want to obtain their footage, notes, or other unpublished work product to use as evidence. For example, in 2012, attorneys for the City of New York subpoenaed Florentine Films in connection with the Ken Burns, Sarah Burns and David McMahon film The Central Park Five, a documentary about the wrongful conviction of five African American teenagers in the highly publicized 1989 “Central Park jogger” rape case. The City demanded outtakes and notes from Ken Burns’ interviews with sources in connection with the City’s defense of a then-pending $50 million civil lawsuit brought by the wrongfully convicted men. Florentine Films moved to quash the subpoena in a New York federal district court under New York Civil Rights Law § 79-h—New York’s statutory shield law— and the qualified reporter’s privilege recognized in that jurisdiction. The federal district court granted Florentine Films’ motion to quash in 2013.

As I’ve previously written in this magazine, a majority of state and federal jurisdictions across the country provide some legal protection to journalists, including documentarians, when it comes to third-party subpoenas targeting their sources and their work product. But those protections vary. Some states, like New York, have enacted specific statutes—so-called “shield laws”—that permit journalists to refuse to comply with a subpoena in certain circumstances; in other states, courts have recognized a constitutional or common law reporter’s privilege. And, while there is no federal shield law, federal courts across the country have recognized the existence of a qualified reporters’ privilege. Because the likelihood of a subpoena is higher in situations where a documentarian has interviewed or filmed parties, attorneys, and other key players connected to a pending civil or criminal case, filmmakers in that situation should plan ahead, and familiarize themselves with what legal protections may—or may not—be available to them in the jurisdiction they are in, in the event they are served with a subpoena. To learn more about the reporter’s privilege and whether or not your state has a shield law that applies to documentary filmmakers, check out the Reporter’s Privilege Compendium, a free, online guide prepared by attorneys at the Reporters Committee.

Lastly, it is important to keep in mind when documenting legal cases that such proceedings—whether civil or criminal—are adversarial in nature. Attorneys and parties in both civil and criminal cases have a vested interest in the outcome of those proceedings and, thus, an incentive to present arguments and evidence to the court (and to you) in the way that best supports their legal positions. As a result, it is not uncommon for parties to present competing—or even diametrically opposed—versions of events, or to present competing experts offering different (and conflicting) expert opinions. For these reasons, it is always a good idea to be skeptical of claims and allegations made in civil and criminal cases, particularly in the early stages of litigation, and to examine the arguments and evidence being presented by all parties to the case.

These are some of the pros (and potential pitfalls) of documenting criminal cases and civil litigation that Reporters Committee attorneys have identified from their work with documentarians and other journalists. While this article can help you be prepared for some of these more common issues, it is not intended to take the place of specific legal advice from a licensed attorney in your jurisdiction. If you are an independent filmmaker who needs assistance finding an attorney, you can always contact the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press Legal Defense Hotline at www.rcfp.org/hotline.

Katie Townsend is Legal Director at Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press.